China’s Sunken Warships – Part 1

Gunboats and the China of the “Inter-War” Years (Part 1)

- Introduction

- Definition of a ‘gunboat’

- China’s Cauldron

- Tracing China’s War Fleet

- China’s Gunboats

- China’s Warship Fleet (listing)

China in the inter-war period, conjures up many stereotypical images. It is evocative of sultry afternoons; of coolie labour; of colonial types whiling away the hours on some shady verandah, or sipping tea under the tropical awning of a ship’s deck

However, this apparent leisured lifestyle with its overtones of Noel Coward is an illusion. It is a world away from the realities of the 1920s and 1930s in China which saw slaughter on a scale hitherto unprecedented.

Left: the gunboat HMS Falcon (or Gannet) 1938. The city of Chungking is visible upper left.

What is not disputed is the iconic image of the gunboat. We have only to turn to the memoirs of those posted to ‘the China Station’ to summon up the atmospherics of that era. Typical is that by G.H. Thomas, “An American in China: 1936-39 A Memoir.” He recalls how he “would frequently have “tiffin” or curry lunch on board with the British officers.” [1] But what is a ‘gun boat’ and why did so many nations have them patrolling up and down China’s coast and along her huge rivers ?

The history of China at first intersects and then collides with that of the 20th century Western world with the impact point being the “gunboat”. Therefore, an understanding of gunboats is essential before moving on to China’s warships of the inter war years.

China’s 20th century history was wracked by decades of internal conflict between War Lords and external warfare with Japan followed by more political tumult and in-fighting. Only now, in the 21st century, a period of calm, growing prosperity and tranquility is its people finding time to explore their cultural heritage and re-examine the roots of the conflicts that shaped the lives of their forefathers.

Symbolic of this resurgence is the salvaging of the Chinese gunboat, Yong Feng. in 1997, from the bottom of the Changjiang River. It was in October 1938 that it was sunk by Japanese fighter planes during what China calls its “War of Resistance against Japan” and which is known in the west as the “Second Sino- Japanese War.”

According to the China ‘People’s Daily’ (May 26, 2008), a specially built berth for the fully restored gunboat has been provided by the town of Jinkou, near Wuhan, the capital of central China’s Hubei Province. (Xinhua/Zhou, Guoqiang). [2] At 836 tons it is a far cry from the European experience of a gunboat, modelled as that is on the British MTB, the German E-Boat and the US PT boats.

Right: the ‘Yong Feng’ (836 tons) later renamed ‘Zhong Shan’).

Right: the ‘Yong Feng’ (836 tons) later renamed ‘Zhong Shan’).

The official China newspaper commentary describes the vessel as a “cruiser”. It is clearly not cruiser sized but of gunboat proportions. This might be a detail ‘lost in translation’ or refer to the way it operated, i.e. cruising along rivers.

Definition of a ‘gunboat’

The lineage of gunboats can be traced back to the Napoleonic war. Originally they were sailing ships. They were shallow draft sloops (if of the larger variety), but could be as small as today’s life boats found on liners. What made them ‘gunboats’ was that they were armed with cannon.[3]

The gunboat, as popular consciousness would today recall them, emerged out of the 19th century and colonial expansion – and in the case of the US, out of their Civil War. They were coal fired and later oil/turbine driven. The film African Queen centres around a German gun boat set in German East Africa at the time of World War I.

A more recent film depicting China in the inter-war years is “The Sand Pebbles” (1966) starring Steve McQueen. Set during the Boxer Rebellion of 1926, it captures the immense rivers, the sheer remoteness of China for repair and re-supply when machinery breaks down and it exemplifies the mood of the time, ie Chinese versus foreigners.

A gunboat is, therefore, any armed vessel, i.e. a small warship regardless of calibre of guns fitted, with a shallow draft, designed for use on rivers and along coasts. Their value lay not only in their comparative cheapness and simplicity of construction but in permitting nation states to project power in places inaccessible to vessels of larger displacement. In that they were the forerunner of the aircraft carrier.

Gunboats were widely employed by all the European powers with colonial ambitions not only in Africa, but in the Far East and Middle East well into the 20th century. The advent of the gunboat was the genesis of gunboat diplomacy in the 19th century; a form of confrontational diplomacy between unequal’s where potential unrest among “the locals” was rapidly quelled by a display of force and fire power along the tribal coastline or inland if large rivers were navigable.

During the Vietnam War (circa 1973), the US Navy used turbine propulsion plants in their Swift and coastal patrol boats along the Mekong Delta. These boats were not heavily armed.

They carried only two.50” calibre machine gun sets and one mortar. Prior to the Vietnam war, the French Indo-China war of the 1960s, saw extensive use of Riverines, brown water craft. There is extensive literature for those interested in French Indo-China wars.

Left: US Navy ‘Swift’ boats in the Mekong.

Left: US Navy ‘Swift’ boats in the Mekong.

Similar measures were used by the British against Indonesian sponsored insurgency against Brunei, Borneo and Sarawak during the Indonesian-Malaysian confrontation, circa 1963. This was countered by SAS units and the Royal Marines. Unlike the French Indo-China conflict a tight lid was kept on publicity surrounding these events.

China’s Cauldron

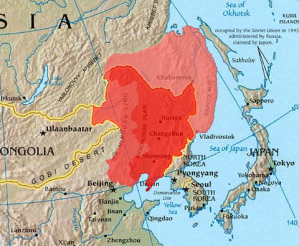

China’s destiny in the 20th century has been dictated by its neighbours in the eastern quadrant – that geographical landmass bordering on Korea, the Sea of Japan, Manchuria and Vladivostok.

The politics in play in this area involved the greed and envy of the Japanese, the gauche ambitions and presumptive Russians, and the rivalry from the Great Powers of Europe, e.g. Britain, France, Germany. Any fleet it might have had has been ravaged by one war after another.

The political realities and potential pressure points are best displayed pictorially by this map (below). The view from Peking would be one of menaces in one form or another Northwards from Russia and Manchuria, and from the east Korea and Japan with the ultimate prize to the victors of Port Arthur and the deep water harbours of the German and British enclaves on the Shantung Peninsula .

Russia

Manchuria

Valivostok

Korea

Japan

Port Arthur

Peking (Beijing)

Shantung Penisular

Manchuria -was rich in basic minerals – the very things that Japan lacked. The local minerals included substantial deposits of iron ore, coal, dolomite and magnesite, aluminous shale and oil shale (petroleum). The oil shale processing operation opened in 1929 and is still (2010) producing an estimated 5,000 barrels of oil per day.

Agriculturally, the Manchurian Plain offered what Japan’s topography could not – a vast expanse of highly productive arable land.

Vladivostok – although strategically located for the Pacific and though the port has been well fortified, its latitude meant it is only open to shipping from April to October of every year. In the winter months ice made it inoperable for the Russian fleet. Russia’s other fleet, facing the Atlantic, suffered the same handicap. Based in the Baltic Sea (and technically Kaliningrad, is in Poland / Prussia), it too was frozen in for several months each year. The hunt for a ‘warm water’ port for its Navy and merchant shipping was therefore a high priority. Russia’s only other option was the Black Sea fleet but it has strategic drawback of being easily bottled up in the Black Sea and reliant on permission to use the Suez Canal and Straits of Gibraltar.

Korea – has figured strongly in both china’s and Japan’s history. In the 16th century it became a unified state (the Joseon era) when Japan was still divided up between warlords. As a result I t was occasionally invaded by various Japanese warlords. By the 1890s Japan had eased Korea out of china’s sphere of influence. Japan increased its control over Korea until in 1910 it annexed Korea after forcing it to sign the Eulsa Treaty of 1905 which made Korea a protectorate of Japan.

It was the friction over Korea that lead to the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) between Qing China perhaps more commonly known as the Manchu Dynasty and Japan. Much of this war was fought on the Korean peninsula and the war gave Japan control of Korea. Japan had by this time acquired Western military technology and forced Joseon to sign an ignominious one-sided treaty.

A process of nation bully learnt first, one suspects, from the American approach to opening up a ‘closed’ Japanese market for trade by gunboat diplomacy in Tokyo Bay (1853), befell Korea and then China. Had the Americans not adopted this posture there would arguably have been no First or Second Sino-Japanese War.

Japan – as we have seen above, Japan had no raw materials, e.g. coal, iron, manganese, nickel, gold, oil, diamonds etc, of its own. In order to start its Industrial Revolution (post 1853) it had to survive by trading. It was entirely reliant upon exports to fund imports and sustain growth. Its military decisions where highly influenced by this economic necessity and mineral availability (the US oil embargo triggered Pearl Harbour 1941).

Port Arthur – as mentioned above, Russia didn’t have a ‘warm water’ port. Vladivostok, St Petersburg, the Baltic and the Barent Sea naval bases all shared the same meteorological conditions – they froze over in the winter. The prospect of acquiring Port Arthur, a warm water port open 12 months a year, was therefore a goal worth striving for and worth the risk of having to pay a high price.

Peking (aka Beijing) – is, like Berlin, a capital city very close (perhaps dangerously so), to inherently belligerent neighbours.

Shantung Peninsula – also spelt Shandong, following the leasing of Port Arthur to the Russians a geographically small part of a Peninsula located opposite Port Arthur was ceded to Germany (on the southern coast) and a second small enclave of Wei Hai Wei to Britain (the most easterly tip) in 1898. Both countries turned fishing villages into major naval stations.

Wei Hai Wei was to become second in importance only to Hong Kong.

It was inevitable that great power rivalry among Europeans states would be played out in this quarter of the world and that the aspirations of nations yet to be acknowledged as world powers would only add the explosive mixture that was the cauldron simmering east of Beijing (Peking).

Tracing China’s War Fleet

Over the many decades the various Chinese dynasties have had a variety of fleets from wooden hulled sail boats without canon, to sailing boats with cannon, followed by metal hulled steam powered craft with fitted cannons.

The following ship information has been gleaned from many web sources including translations from modern Chinese sites. However, Battleships-Cruisers.co.uk is a very comprehensive listing of naval craft from around the world and painstakingly put together. The Chinese subsection can be found at (http://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/chinese_navy.htm). [4] In an attempt to secure the best possible data base even the sites of model makers have been examined for any relevant details specific to any models that they might produce.

The sophistication of China’s navy was never cutting edge (unlike Japan’s) and it lagged behind that of the ‘great powers’.

The sophistication of China’s navy was never cutting edge (unlike Japan’s) and it lagged behind that of the ‘great powers’.

Left: the Kai Che, 1889 (2,100 tons).

It did, however belatedly, begin to reflect advances in naval technology first made in the West.

The range of ships available to China during the Second Sino- Japanese War (1931 – 45) stretched from ships similar to the Kai Che to the modern ‘Ning Hai’ class light cruiser

The range of ships available to China during the Second Sino- Japanese War (1931 – 45) stretched from ships similar to the Kai Che to the modern ‘Ning Hai’ class light cruiser

Left: the Ping Hai, 1934.

At 2,500 tons and 360 feet long, the ‘Ping Hai’, and her sister ship the ‘Ning Hai’ was too big to be termed a gunboat and a little shy of a destroyer. In the World War II era it would probably have been categorised as a Frigate or Corvette.

The matter of weight/ displacement is an interesting one. It does not apply to warships these days as the armaments carried on Corvettes, Escorts, Destroyers, Frigates, Fast Patrol Craft

|

Table 1. Warship classification (post Washington Naval Treaty)

|

|

| Battleship | less than 35,000 tons (less than 16” guns) |

| Heavy Cruisers | + 10,000 tons (8” guns) |

| Light Cruisers | 5,000 – 10,000 tons (6” guns) |

| Destroyers | 3,000 – 4,000 tons |

| Frigates: | 1,100 – 3,000 tons |

| Corvettes: | 500 – 1,100 tons |

| Fast Attack Craft (MTB): | +25 Knots |

| Large PC | 100 – 500 tons |

| Coastal PC | less than 500 tons |

| Source: http://www.defencethink.co.za/node/200 | |

etc, are all very similar in lethality.

Following the Washington Naval Treaty (1921), the tonnage of World’s naval forces was limited and the size of ships classified as detailed in the table (left).

Problems arose immediately with Japan which ignored it; Italy lied about the displacement of their new ships; and Germany which in the case of Pocket Battleships complied with heavy cruiser tonnage requirements but fitted 11” guns.

Exploiting loopholes in the Versailles Treaty and later the Washington Treaty, for instance, yielded Germany craft such as the E-Boat which re-wrote naval warfare and were a match for any destroyer, frigate or corvette. China was acquiescent at this time of peace and Naval Treaties whereas Japan was not.

It is difficult to imagine – given the attrition in combat suffered by European nations in World War II – of another navy so readily prepared to fruitlessly sacrifice ships on a scale of the Chinese yet which had a warship from 1904 that was still operational and had not been scrapped or sunk by 1963. Nonetheless, that is the record of the sloop Chiang Yuan shown in the table below of “Chinese Gunboats.”

The Chinese warship losses in the 20th century and specifically in the inter war years were even grerater than the losses suffered by Britain’s Royal Navy (1939-45) which lost appro. 50% of its surface fighting ships, principally in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic theatres of war. Arguably, Japanese losses by 1945 were comparable, however, the latter period was marked by a sacrificial attitude by the Japanese to the use of warships ( e.g. the last voyage of the Yamato, 72,000 tons, April 6th 1945).

NB. an alphabetical listing of Chinese warships, spanning almost 100 years is available in Part 5 (https://rwhiston.wordpress.com/2010/06/02/6/).

Almost all Chinese naval ships and gunboats of this era were steam driven; some were paddle-steamers, other had propellers. The term sloops which appears on some lists applies to only a handful of craft and might wrongly imply in the reader’s mind a sailing ship, which was not the case.

China’s Gunboats

A reading of the following table of ships makes for grim reading. The fate of every ship is either sunk or scuttled. The tedium is only interrupted by the occasional ‘capture’ or refloating.

Destruction of ships is in the nature of naval warfare but in China’s case there is no counter balancing losses to the enemy, i.e. the Imperial Japanese fleet.

Glancing down the list one is driven to conclude that far from losing ships during decisive sea battles the Chinese of that time preferred not to commit too many assets. The result was that those that were committed were in no better position than if they had been thrown to the wolves. In their defence it has to be stated that many of the Chinese combat vessels had shallow drafts and so would not be suited to sustained open water engagements.

There are valid military reasons for adopting a “Fleet in Being” posture, ie not committing one’s fleet. This tactic has been shown to be successful but it was not the strategy to adopt on this occasion for very obvious reasons (see Part 2 for Fleet in Being).

One can only further speculate that the lack of any co-ordinated air cover led to a defensive mind set where scuttling otherwise useful ships would at least hamper the enemy.

At the close of the 19th century the Imperial Chinese Navy had two battleships, the Ting Yuan and Chen Juen (Chen Juan), which were recognised as among the most advanced battleships of their time. Completed in 1895 they were rated as good, if not better, than any ship in the fleets of Great Britain and Germany.

Both the Ting Yuan and Chen Juen were ‘armoured turret’ ships and both had an armoured belt 30-centimetre (1ft) thick which experts said was resistant to the firepower of anything available at the time.

Armaments consisted of 4 × 12” guns, 2 × 6” guns, 2 × 57 mm guns, 2 × 47 mm guns, 8 × 37 mm guns and 3 × 14” torpedoes all carried at 14 knots and weighing 7,670 tons. Yet by February 1895 Ting Yuan had been sunk and Chen Juen captured by the Japanese navy

One of the most startling differences with Western navies is the sheer inconsistencies in naval shipbuilding. There seems to be no programme of building 6 or 10 ships of a similar design (a class), to aid cost reduction and speed of assembly.

Where there are signs of progress towards systematically building ships it is interrupted by either Japanese aggression (1931), the Sino-Russian War (1929), or sanctions against German (1939). In the case of the Ping Hai, her anti-aircraft guns were not delivered by Japan due to the Mukden Incident of 1931 (German guns had to purchased to replace them). When ordering MTB boats (E-boats) from Germany the order for 18 is caught up in the confusion as World War II broke out.

China is a huge country with hundreds if not thousands of navigable waterways (brown water rivers). It is not surprising that its naval forces are therefore divided up into the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Fleets located at different points along its huge coastline.

Cataloguing China’s navy at first gives the impression of huge fleets but in reality the attrition in the 1st and 2nd Sino-Japanese Wars substantially reduced the numbers operational. In common with the Spanish Republic (also in 1937), China appears not to have bought wisely – and those vessels that had survived from previous conflicts are of such a vintage as to be liabilities.

It shares with the Spanish Republic’s experience a lack of audacious action by its captains and a central command vacuum. It is the Far Eastern reflection of a weak state unprepared for war and with no air power to suppress attacks on its shipping or its civilian population.

To have so few modern vessels – and to lack deep water experience – indicates a lack of central control and a lack of understanding of how military power was projected in the early 20th century. China founds itself unable to pose a threat to Japanese landings, or to harass troopships or jeopardise supply lines. Nor was it in a position to make a surprise, if token, attack on the Japanese mainland, e.g. as American colonists had done, crossing the Atlantic to fire on an English port.

China may have a long coastline but its large land mass is hemmed in on 3 sides by land occupied by not always peaceful neighbours. It does not have the luxury – as Japan and Britain enjoy – of the neutrality of the seas or oceans on all its perimeters. Was it this, or economic impotence, that led to the relegation of naval power in preference to land forces ?

Gunboats might be the smallest vessels in any navy but as illustrated in the opening remarks they have always played a pivotal role, especially in SE Asia, in severing the opponent lines of communications, cutting off retreats and inserting fighting forces behind enemy lines.

So far, this commentary has focused on gunboats of the Chinese Navy but other nation’s navies also had gunboats in and around China. The gunboats of these navies will be dealt with separately. I apologise to the reader for any ambiguity or lack of clarity they may come across here and there in the table below. The reason for this is that certain aspects are contradictory. For instance, modern Chinese spelling seems to vary from the traditional Chinese spelling that appears in texts book, e.g. Kiang Yuan or Chiang Yuan or Chiangyuan. If a ship listed as the Lien Chung could it really be a misspelling for the Lieng Chung, or is it vice versa ? It is not uncommon for boats to be renamed, e.g. Yong Feng became the Zhong Shan but the modern Chinese spelling of these names appears to be Yongfeng and Zhongshan. The Vaterland (captured by China in March 1917) is a case where it was renamed Li Chien or Li Sui depending on source.

Legend : Where contradictions have arisen I have endeavored to marked them with a “ / ” indicating an alternative answer. This sometimes applies to the date and location of the sinking – one source will claim it as, say, 1937 and another 1938; one in, say, Aug, and one in Sept.

A ship may be launched the same year and have approx the same displacement recorded with two similar names but spelt slightly differently. Conversely, identical ships (by name) can be found to have different launch dates, different tonnage, and different speeds and armaments. This table can only point up the difference where they occur and does not seek to arbitrate.

Where ‘aka’ (Also Known As) is typed, this does not imply a definite known alternative name but a suspicion/questioning of competing data. Any future confirmation from readers should be sent using the message/reply panel at the foot of the page and will be most appreciated.

|

|||||||||

| Operating between 1918 and 1939– in date order of construction | |||||||||

| Name | Launch/ Laid down | Length | Displacem’t | Speed (knts) | Engine | Main Guns | Torpedo / Secondary | Fate | |

| Fei Ying class (1898) Reclassified as destroyer by 1930 | |||||||||

| Fei Ying | 1895Yarrow Built | 246 ft | 837 / 850 tons | 22 | steam | 2 x 4”6 x 2” (57 mm) | 3 x 14” | Sunk 1932 | |

| Chien An class [ by tonnage, this is frigate / destroyer size ] | |||||||||

| Chien An | 1900 | 225 ft | 861 / 900 tons | 23 | steam | 1 x 4”3 x 76 mm6 x 37 mm | 2 x 14” | Rebuilt 1930, renamed Ta Tung. Scuttled in 1937 | |

| Chien Wei | 1900 | 225 ft | 861 tons | 23 | steam | 1 x 4”3 x 76 mm6 x 37 mm | 2 x 14” | Rebuilt 1930, renamed Tse Chion | |

| Chiang Yuan class [ aka Kiang Yuan ] [ this is frigate / destroyer size ] | |||||||||

| Chiang Yuan | 1904 | 177 ft | 565 tons | 13 | steam | 1 x 4.7”1 x 75 mm4 x 47 mm | Scrapped 1963 | ||

| Chiang Hung | 1907 | 177 ft | 565 tons | 13 | steam | 1 x 4.7”1 x 75 mm4 x 47 mm | Wrecked 8th Sept 1931 | ||

| Chiang Li | 1907 | 177 ft | 565 tons | 13 | steam | 1 x 4.7”1 x 75 mm4 x 47 mm | Scuttled 26 Sept 1937 | ||

| Chiang Chen aka Kiang Chen ? | 1907 | 177 ft | 550 / 565 tons | 13 | steam | 1 x 4.7”1 x 75 mm4 x 47 mm | Damaged by aircraft Salvaged / Sunk 20 July 1938 / Fate not known | ||

| Hu Peng class – torpedo boat [ Hu Ngo renamed Kawasemi by Japanese # ] | |||||||||

| Hu Peng aka Hupeng | 1906 | 135 ft | 96 / 97 tons | 23 | Coal | 1 x 2.5” (65 mm) | 3 x 14” torpedoes | Sunk 1 / 3 Oct 1937. Yangtze River ? | |

| Hu Ngo # | 1906 | 135 ft | 96 / 97 tons | 23 | Coal | 1 x 2.5” (65 mm) | 3 x 14” torpedoes | Sunk 8 Oct 1937 / Renamed Kawasemi | |

| Hu Chung | 1906 | 135 ft | 96 / 97 tons | 23 | Coal | 1 x 2.5” (65 mm) | 3 x 14” torpedoes | Sunk 3rd Oct 1937 | |

| Hu Ying | 1906 | 135 ft | 96 / 97 tons | 23 | Coal | 1 x 2.5” (65 mm) | 3 x 14” torpedoes | Sunk 8 Oct / Aug 1937 | |

| Hu E # | Also reportedly renamed Kawasemi | ||||||||

| Chi Fiungo | 1906 | Sunk 8 Oct 1937renamed Kawasemi scrapped 1939 | |||||||

| Chu class [Kawasaki Yard., Kobe] | |||||||||

| Chu Tai | 1906 | 200 ft | 740 / 752 tons | 13 | steam | 2 x 4.7”2 x 76 mm 2 x 25 mm | – – | Wrecked / damage by aircraft 1 June 1938 Yangtze | |

| Chu Tung | 1906 | 200 ft | 740 tons | No details | – – | Discarded 1960s | |||

| Chu Chien | 1906 | 200 ft | 740 tons | No details | – – | Scuttled 11 Aug 1937 | |||

| Chu Yu # | 1907 | 745 / 740 tons | No details | Sunk 29 Sept 1937 | |||||

| Chu Yiu | 1907 | 740 tons | No details | Sunk 2 Oct 1937 | |||||

| Chu Kuan aka Chu Kwan | 1907 | 200 ft | 740 tons | No details | Stricken 1960s | ||||

| Kuan Chuan class | |||||||||

| Kuan Chuan | 1908 | No data | Stricken 1929 | ||||||

| An Feng class | |||||||||

| An Feng | 1908 | No data | Not Known | ||||||

| Chiang Kung class | |||||||||

| Chiang Kung | 1908 | 250 tons | Sunk Oct 1938 | ||||||

| Chiang Tai | 1908 | 250 tons | Sunk 26 Sept 1937. Sink in Hengmen | ||||||

| Lieng Ching class (see also Lien Chung [spelling error ?] The latter was also launched in 1910 and sunk on 26th Aug 1937) | |||||||||

| Lieng Ching | 1910 | No data | (1937 ? ) | ||||||

| Yong Feng aka Zhong Shan [ ordered from the Mitsubishi Shipyard ] [modern Chinese spelling of this appears to be Yongfeng and Zhongshan ] (raised 1997 & pictured above). | |||||||||

| Yong Feng | 1910 | 836 tons | 200 ft | 13 | Sunk by 6 aircraft, 24 Oct 1938 | ||||

| Chiang His class | |||||||||

| Chiang His | 1911 | No data | Not Known | ||||||

| Chang Feng class (1911) | |||||||||

| Chang Feng | 1911 | 198 ft | 390 tons | 32 | Steam | 2 x 3” (76mm)3 x 47mm | 2 x 18” | Wrecked 1932 | |

| Fu PoSee also Chi Fu Po | 1912 | 198 ft | 390 tons | 32 | Steam | 2 x 3” | 2 x 18” | [ Sunk 9 / 1937 ? ] | |

| Fei Hung | 1912 | 198 ft | 390 tons | 32 | Steam | 2 x 3” | 2 x 18” | – – | |

| Chiang Hsi class [Is this a misspelling of the Chiang His and/or Kiang Hsi class above ? ] | |||||||||

| Chiang Hsi | 1911 | 146 | 140 tons | – – | Sunk 24 Aug 1941 | ||||

| Chiang Kun | 1912 | 146 | 140 tons | Sunk 24 Aug 1941 | |||||

| Yung Hsiang class [ by tonnage, this is frigate / destroyer size ] | |||||||||

| Yung Hsiang | 1912 | 780 tons | – – | Scuttled 26 Sept / Aug 1937 Later raised | |||||

| Yung Feng | 1910 / 1912 | aka Chung Shan | 780 tons | See below | Sunk 24 Oct 1938 | ||||

| Wu Feng Cantonese gunboat | |||||||||

| Wu Feng | 1912 | 200 tons | Scuttled 11 Aug / 26 Sept 1937 Sunk near Modaomen | ||||||

| Yung Chien class [ by tonnage, this is frigate / destroyer size ] [Yung Chien was renamed Asuka and Yung Chi was renamed Hai Hsing by the Japanese ] Kiangnan Dock. | |||||||||

| Yung Chien | 1915 | 215 ft | 860 tons | 13 | steam | 1 x 4”1 x 3”3 x 47 mm | Sunk by aircraft, 25th Aug 1937 Captured Nov1937. Re-used by | Japan as AA ship Asuka. Sunk in Huangpo Estuary, Shanghai, May 7, 1945 | |

| Yung Chi | 1915 | 215 ft | 860 tons | 13 | steam | Sunk 21 Oct 1938, Yangtze Refloated by Japan as Hai Hsing. Survived the war. | |||

| Chien Hung class | |||||||||

| Chien Hung | 1915 | No data | Not Known | ||||||

| Chien Chung class [aka Chieng Chung ?] river gunboat | |||||||||

| Chien Chung | 1915 | 110 ft | 90 tons | Paid off 1931 | |||||

| Yung An | 1916 | 110 ft | 90 tons | Paid off 1931 | |||||

| Kung Chen | 1916 | 110 ft | 90 tons | Sunk Oct 1938 | |||||

| Hai Yen class river gunboat | |||||||||

| Hai Yen | 1917 | 165 ft | 56 tons | Sunk 29 July 1937 | |||||

| Hai Fu class river gunboat | |||||||||

| Hai Fu | 1917 | 105 ft | 166 tons | – – | |||||

| Hai Ou | 1917 | 108 ft | 166 / 227 tons | – – | |||||

| Hai Hung class | |||||||||

| Hai Hung | 1917 | 112 ft | 190 tons | – – | |||||

| Hau Ku | 1917 | 112 ft | 190 tons | Sunk Sept 1937 | |||||

| Ex – German river gunboat. Formerly the Vaterland captured March 1917. Renamed Li Chien or Li Sui depending on source. She joined Manchukuo Navy at Shanghai in 1932. There is a sister ship to the Vaterland, the Tsingtau [?], though strictly speaking she was never part of the Chinese fleet. The Otter was re-named Li Sui or Li Jie depending on source. (gunboat “Lee Swei” (SMS Vaterland), gunboat “Lee Jeh” (SMS Otter) | |||||||||

| Li Chien ex –VaterlandOne Chinese source says the Lee Swei was Vaterland | 1903 acquired 20/3/ 1917. German shipyard Elbing’s Schichau | 158 / 155 ft | 170 / 280 / 359 tons | 13 | Coal | 2 x mm cannons | 3 x m/guns ? ? | Captured by Chinese March 1917. Refloated and repaired by Japanese, in 1931. Re-named Ji Sui 1937 Stricken 1942 | |

| Tsingtau | 1903 | Scuttled 21 March 1917 | |||||||

| Li Sui or Li Jie ex – Otter“Lee Jeh” said to be Otter | 1909 acquired 20/3/ 1917 | 177 /165 ft | 266 / 314 tons | 14 | Coal | 1 x 88 mm howitzer | 2 x Rapid fire 5.2 mm50 mm cannon, 3 x m/guns. | Taken 20 March 1917. Broken up 1932 / Scrapped 1942 | |

| Li Jie ex -German boat Otter. Built in Germany, | May 1904 / 1909 Nian Tecklenborg | 266 tons | 14 | Coal | As above | ||||

| Hai Ho class river gunboat | |||||||||

| Hai Ho | 1917 | 105 ft | 166 / 211 tons | – – | |||||

| Hai Peng aka Hai Bung | 1920 | 108 ft | 211 / 227 tons | – – | |||||

| Ships built post World War I | |||||||||

| Hsien Ning class | |||||||||

| Hsien Ning | 1928 | 418 tons | Attacked by aircraft in Yangtze. Fate not known | ||||||

| Ming Huen class | |||||||||

| Ming Huen | 1929 | 196.7 ft | 550 tons | – – | |||||

| Yung Sui class (Yong Sui ?) | |||||||||

| Yung Sui | 1929 | 224 / 215 ft | 650 / 860 tons | 18 | Coal | 1 x 6”,1 x 4.7” 3 x 3” | Multiple m/guns | Decommissioned in 1970 ? | |

| Ex- Italian MTBs [purchased] | |||||||||

| No 1 (ex – Mas 226) | Purchased 1921 | Stricken 1933 | |||||||

| No 2 (ex – Mas 227) | Purchased 1921 | Stricken 1933 | |||||||

| Yat Sen class | |||||||||

| Yat Sen gunboat. Cost 3 million yuan | 1930 | No data | / 1,650 tons | 19 | Coal | 140 mm main gun. 75 mm anti-aircraft. 4.47 mm rapid-fire cannon | No torpedo tubes / Beached after damaged by aircraft. / | Salvaged by Japan.Re-named Atada & used for training Captured by Allies Aug 1945. | |

| Cantonese Navy torpedo boats | |||||||||

| No. 1 | Sunk Oct 23 1937 | ||||||||

| No. 2 | Sunk Oct 23 1937 | ||||||||

| No. 3 | Sunk Oct 25 1937 | ||||||||

| No. 4 | Sunk Oct 23 1937 | ||||||||

| Coastal Patrol Boats (MTBs by Thornycroft, UK, 18 ordered) (some delivered in 1938) This small MTB section is full of conflicting evidence. See also ‘Swift Boat’, History 102 , Cloud boats, History 181, History 223, Pu-Star, Yang Weizhi, Electric Ray Schools, Shi Kefa Squadron, Wen Tianxiang squadrons, All Electric Boat, Jie Wei, History of 34, Jiang Xiang Ao, Xie Yan pool, Yen 52, 92 Yen). History 34, History 102, History 223, History 181 /Man 42, Man 93, Shi rong, Man 88, Xie Yan pool, /Man 53 / Yen 171, Man 171, Yen 161, Yen 92, Yen 164, (http://60.250.180.26/ming/2803.html) | |||||||||

| Swift Boat No. 1 | 1934 | 55 ft | 14 tons Wood | 40 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | – – | |

| Swift Boat No. 1 | 1934 | 55 ft | 14 tons Wood | 40 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Shi / aka History Boats ? | |

| Jian Kang / Jiankang | Is this Chien Kang ? | 390 tons | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Sunk by aircraft Sept 26, 1937 near Jiangyin | ||||

| This following section incorporates what is thought to be Thornycroft MTB style gunboats | |||||||||

| History 102 / Shi 102 ? | 1936 Thornycroft | 55 ft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x1 8 “ torpedoes | Sunk Aug 16, 1937 attacking Japanese cruiser Izumo | |

| Shi 181 / History 181 | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Damaged Oct 12, 1937. Sunk in Yangzi Nov 11, 1937 by Japanese vessels. | ||

| Shi 34 / History 34 aka “Jiang Xiang Ao | 1936 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Damaged Oct 12, 1937 / Sunk Jiang Xiangao Sept 29 1937 | ||

| Shi 223 aka Chen Puxing ? | 1936 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Sank July 17 1938 after an accident | ||

| History 223 | Is this Shi 223 ? | – – | |||||||

| History 181 | Thornycroft ? | – – | |||||||

| Pu-Star | Thornycroft ? | – – | |||||||

| Wen 42 Huang Zhenbai | 1936 Thornycroft ? | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Damaged 17 July 1938. Scuttled in Guangxi in Sep 1944? | ||

| Wen 88 aka Xie Yanchi | 1936 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Damaged July 17, 1938 Scuttled in Guangxi in Sep 1944? | ||

| Wen 93 aka Wu Shirong Aka Shi-rong | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | Attacks and damaged IJN minelayer Kamome | Sunk by Japanese on 14 July 1938 | ||

| Wen 171 aka Liu Gongdi | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Scuttled in Guangxi in Sept 1944 ? | ||

| Yan 53 | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Scuttled in Guangxi in Sept 1944? | ||

| Yan 92 | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Cornered and captured in Oct 1938 by Japanese vessels at Sanshui | ||

| Yan 161 | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | Damaged Aug 1, 1938 | Scuttled in Guangxi in Sept 1944? | ||

| Yan 164 | 1934 Thornycroft | 14 tons Wood | 40.3 | Petrol | Four mines, twin m/guns | 2 x 18“ torpedoes | Scuttled in Guangxi in Sept 1944? | ||

| This following section incorporates what is ALSO thought to be MTB style gunboats –but this could be wrong | |||||||||

| Tun Ri | Sunk Aug 26, 1937 | ||||||||

| Chong Ning | Chongning / Chang Ning ? | Damaged June 29, 1938. Sunk July 9 1937 / 3 July 1938 | |||||||

| Xian Ning / Xianning ? | 1929 gun boat | 180 feet , | 418 tons | 16 | Coal | 1 x 4.7” guns,1 x 3” 1 x 84 mm anti-aircraft gun | 57 mm Sushe Pao 2, 20 mm cannon Oregon 2. | Sunk by aircraft July 1, 1938 | |

| Yixian | 1,500 tons | Sunk by aircraft Sept 26, 1937 at Yonganzhou | |||||||

| Sheng class patrol ships – Canton Fleet | |||||||||

| Kung Sheng. | Converted into gunboat June 1928 | – – | |||||||

| Yi Sheng / Yisheng ? | 1911 | Converted into gunboat Jan 1928 | Sunk Nov 11, 1938 | ||||||

| Jen Sheng | new | Converted into gunboat | – – | ||||||

| Shun Sheng | 1911 | Shunsheng | Converted into gunboat Dec 1929 | – – | |||||

| Yung Sheng | 1908 | Yungsheng | Converted into gunboat March 1928 | – – | |||||

| Ren Sheng / Rensheng Aka Yensheng | Same class | Converted into gunboat June 1928 | Sunk Nov 11, 1938 | ||||||

| German Patrol Boats (Schnell Boats) (Ordered but possibly not all delivered by time of outbreak of European war 1939. Ref: Chow 22 Chow Chow 371 Yue Fei unit 253). | |||||||||

| Yue 22 # Aka Qihong Zhang | 1936 [?] | 92 ft | 54 tons | 34 | Diesel | 1 x 20 mm m/gun | 2 x 21” torpedoes | Sunk Aug 1st 1938 / Oct 1938 by Japanese planes | |

| Yue 253 aka Cui Tao,/ Cui Zhidao | 1936 [?]aka No. 1 PT Boats ‘Sea Whale’ | 92 ft | 54 tons | 34 | Diesel | 20 mm m/gun | 2 x 21” torpedoes | Retreated to Sichuan. Survived the war. Decom-missioned. 1963 [?] | |

| Shi 253 E-boat | 1936 [?] | 92 ft | 54 tons | 34 | Diesel | 20 mm m/gun | Renamed “Fast 101” on April 23 1949. (Sea Whale ?) | Damaged 17 July 1938 | |

| Yue 371 aka Li Yu-xi / Li Yuxi | 1936 [?] | 92 ft | 54 tons | 34 | Diesel | 20 mm m/gun | 2 x 21” torpedoes | Retreated to Sichuan. Survived the war. | |

| Ping Hai class – listed by Chinese as ”Cruisers”http://www.worldweapons.eu/1-Warships/China/index_warship_china.html | |||||||||

| Ping Hai | 1936 | 360 ft | 2,448 tons | 23 | Oil | 3 × double 5.5” suspect | 6 × 76 mm (3 “) AA gunsNo Float planes | Sunk Sept 22 1937 but refloated as Yasoshima Sunk again at Leyte Gulf Nov 1944 | |

| Ning Hai / was Hai Rong meant to be sister ship ? | 1932 | 360 ft | 2,448 tons | 23 | Oil | 3 xdouble 5.5”6 × 76 mm (3 “) AA guns | 4 x 21” torpedoes2 x Floatplanes 4 x m/guns | Sunk Sept 23 1937 but refloated. Renamed Ioshima / ‘500 Islands’. Sunk again by US 19 Sept 1944 | |

| Sources: http://www.worldweapons.eu/1-Warships/China/index_warship_china.html and ‘Battlefleet 1900’ http://www.wtj.com/games/battlefleet_1900/ships_cn.htm , http://www.gwpda.org/naval/fdzz0001.htm and http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=101&t=75151&start=30 and http://www.navypedia.org/index.htm http://www.hslmouldings.co.uk/thornycroft_mtb.htm / http://60.250.180.26/ming/2803.html / , http://www.warship.org/wi_index2.htm, and http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_65836e7b0100gta6.html and http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/sino-japanese-1938.htm , http://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/chinese_navy.htm and http://www.navypedia.org/ships/japan/jap_dd_yamasemi.htm , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_cruiser_Ioshima , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_cruiser_Ping_Hai , http://homepage2.nifty.com/nishidah/e/s_index.htm Torpedo boats http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=101&t=75151&start=90, http://www.navypedia.org/ships_index.htm | |||||||||

Attrition Rate

Some sources state that by 1937 (several year after the beginning of the Second Sino- Japanese War), the Chinese Navy totalled only 59 vessels. The largest of these was a group of six light cruisers, none of which exceeded 3,600 tons.

Supporting these were 30 gunboats and a miscellaneous collection of 23 smaller craft, MTBs, sloops and transport vessels etc, giving a total of approx. 90 ships of assorted sizes.

Most of these were sunk in the Yangtze, at Shanghai, Tsingtao and Canton during Aug and Sept 1937. Another culling occurred in the autumn of 1938.

Almost all Chinese ships fell victim to Japanese air power, strafing, bombing and artillery fire. The reason for this will be explored in Part 2. Those that were damaged were then used as block ships but so too were many seaworthy ships. The reason for this is difficult to at first fathom.

Some of the vessels that were beached were later salvaged by the Japanese (see notation in Table I and 2). Curiously while some ships did not last long in Chinese hands, or gave unsatisfactory service, two light cruiser used by the Japanese, the Ping Hai and the Ning Hai did exceptionally well in Japanese hands.

By the end of the war China reportedly had only one torpedo boat and 13 river gunboats (though sources here also conflict and the new Communist regime at eh time was not open about such matters).

However, it would appear that five of these gunboats were former British, American and French craft, transferred when their Western crews “had crossed overland to from Burma.” This would not make sense. It is more likely that the crews abandoned their boats up rivers away from the Japanese Army/occupation and headed north around Indo-China and Malaya (again to avoid the Japanese occupation) and marched into northern India and Burma. [5]

The topic of attrition would not be complete without including the part played by ‘cliques’ within China during this period. Every faction was struggling for supremacy. The Nationalist Government was facing threats from within its own ranks, from regional War Lords, from ambitions metropolitan politicians and the ever-present danger posed by a growing Communists party.

All this was in addition to the threat posed by the Japanese Imperial forces and an ambivalent attitude by major trading nations around the world. Chinas, when it could overcome a world hotly embracing appeasement and non-interventionist policies, found its orders from Germany were overtaken by Japan’s alliance with Germany or quarantined by the Allied power in 1939.

Now go to Part 2 of ‘China’s Sunken Warships’ for more ships and Tables

[1] “An American in China: 1936-39 A Memoir” http://www.willysthomas.net/ChungkingInfo.htm

[2] Press Release http://www.lcsd.gov.hk/en/ppr_release_det.php?pd=20030123&ps=04 and People’s Daily, May 2008 http://english.people.com.cn/90001/90783/91300/6419821.html.

[3] The small gunboat went through a variety of forms before taking their final form in 1805. These boats, designed by Commissioner Hamilton, varied from 43 to 51 tons, and normally carried three guns – two in the bow and one in the stern, all 18-pounders. http://www.reference.com/browse/gunboat

[4] Other useful sites (URLs) can be found at the foot of the table, eg ‘Naval-History.net’ http://www.naval-history.net/index.htm. The Chinese sub-section can be found at (http://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/chinese_navy.htm).

[5] Source: http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=101&t=75151&sid=93fc4d9a6004e9cd308407f8b0b880a4