International Naval Intervention and Protection Force 1936

By Robert Whiston FRSA. Feb 2010

It is not widely appreciated that the Second World War very nearly began not in 1939 but in 1937.

A commentary on the array of international naval forces deployed for the evacuation and subsequent patrolling of Spanish waters, 1936 – 1939.

Contents:-

1. International Alarm

2. List of Warships

3. Strategic Location

4. Evacution of Foreign Nationals

5. List of Mechantmen

6. Spanish Naval Forces

7. Submarines

8. Photo Gallery

9. How pivotal was Gold ?

10. Sources and References

Footnotes

The Spanish Civil War is perhaps both the most controversial yet most forgotten conflict of the 20th century. At its height it tied up the majority of the British Home Fleet and a sizeable proportion of the French Navy.

The reason why the civil war nearly triggered an early start to a World War is two fold; Spain is uniquely positioned astride the great trading routes of the world and secondly the intensity of the hostilities.

The belligerent on both sides, namely the Republican Gov’t forces and the Nationalist fascist (the rebel faction) under Franco both completely ignored international maritime law whenever it suited them.

For instance, this unfettered behaviour saw 18 Dutch, 26 Danish, and 30 Norwegian ships have their cargoes confiscated between November 1936 and April 1937. Other nations suffered similar fates and saw entire ships confiscated.[1] Some were even torpedoed and sunk.

The international community, lead by France and Great Britain, set up an international maritime protection force to counter ships being captured as “prizes”. Beginning in late 1936 actions was taken to avert the blockading of ports to neutral shipping and the wanton attacks on merchantmen in international waters.

Along the Mediterranean coast 50 destroyers were constantly on station to deter submarine attacks – principally from Italian submarines with Spanish officers on board.

Up to 80% of the Royal Navy’s destroyer force was engaged in Spanish coast intercepts and patrolling. Comparable numbers are not available for the French Fleet.

Initially, German and Italian warships assisted in evacuating foreign nationals and patrolling the coast but gradually became very involved in coastal bombardment and torpedoing of both Republican bound shipping and third nation warships.

To deter the menace of submarine activities the Nyon Agreement of 1937 required 27 destroyers to patrol along Spanish coastlines to enforce safety.

Great Britain’s Royal Navy was joined by the large resources of the French fleet together with elements from Italy, the United States, Argentina, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Holland, Norway and Yugoslavia.

The Spanish Civil war is probably the first time aerial power was shown in war conditions to be decisive against a capital ship when on 29th May 1937 bombers of the Republican Gov’t attacked and damaged the German pocket battleship Deutschland. The two Tupolev SB-2 “Katyusha” bombers, piloted by two Russians, inflicted significant damage with 31 (some report 22) fatalities and some 101 wounded. This new dimension for aerial warfare precedes the attack on Taranto and Pearl Harbor by a good margin.

The First World War had seen the emphasis placed on waterline defence against torpedoes and heavy calibre shells. By the 1930s it was being realised in naval circles that existing naval ships were vulnerable to aerial attack.

The pictue of HMS Delhi (left), launched in 1919, shows how deck armour on ships of that era were of minimal thickness providing no protection from bombs or high angled incoming shells. This was to prove the undoing of HMS Hood and later HMS Repulse.

The pictue of HMS Delhi (left), launched in 1919, shows how deck armour on ships of that era were of minimal thickness providing no protection from bombs or high angled incoming shells. This was to prove the undoing of HMS Hood and later HMS Repulse.

Left: Bomb damage to the stern of HMS Delhi during operations in North Africa (1942).

The scale of, and the potential as a flash point, is normally underplayed. At one point HMS Coventry and HMS Curlew led a 70 strong destroyer flotilla gathered in the western Mediterranean to suppress the submarine menace. [2] Of those 70 destroyers, 45 were British with more British and ‘non-interventionist’ warships in the Bay of Biscay, near Bilbao and along the Galician coast.

The following is a list of some of the Royal Navy warships that took part in patrolling and interdiction actions from 1936 to 1938 – 39. Where it has been possible, ships of other Navy’s are also included. The last two columns on the right show any known engagement during the Civil War followed by the fate of the ship during World War II. The citation “bombed” does not mean the ship was hit. Aerial bombing was, in 1936, still primitive and most bombs missed their target.

The same appears to be true of torpedo launches. In one engagement 12 were fired but only 3 came close to hitting the intended target. Indeed, salvos from one Spanish warship and intended for another opposing Spanish warship straddled an onlooking British warship.

| Navies – Intervention Force, Spain 1936 – 1939 (by navy and ship) | ||||

| Navy | Spain 1936-39 | World War II | ||

| Royal Navy | Type | Ship | Attacked | Fate |

| Royal Navy | B class destroyer | HMS Basilisk | Sunk 2-1941 | |

| HMS Blanche | Attacked by Nationalist bombers | Sunk 11-1939 | ||

| HMS Boreas | Attacked by Republican planes | Loaned to Greece 1944. Scrapped 1952. | ||

| HMS Brazen | Sunk 7-1940 | |||

| HMS Brilliant | Scrapped 2-1948 | |||

| C class destroyer | HMS Kempemfelt | Scrapped 1952 | ||

| HMS Comet | Scrapped 1945 | |||

| E class destroyer | HMS Encounter | Sunk 3-1942 | ||

| HMS Electra | Sunk 2-1942 | |||

| F class destroyer | HMS Forester # | Scrapped 6-1947 | ||

| HMS Foxhound | Fired on by fascist ship 8-1937 | Scrapped 5-1946 | ||

| HMS Firedrake | Sunk 12-1942, | |||

| HMS Fame | Scrapped 1968 | |||

| HMS Fortune | Scrapped 1946 | |||

| G class destroyer | HMS Greyhound | Sunk 5-1941 | ||

| HMS Grafton | Sunk 5-1940 | |||

| HMS Gallant | Attacked by Republican planes 3-1937 | Crippled 1-1941 | ||

| H class destroyer | HMS Hardy | Sunk 4-1940 | ||

| HMS Hunter | 5-1937 Hit by mine. 8 dead | Sunk 4-1940 | ||

| HMS Hyperion | Sunk 12-1940 | |||

| HMS Havock | Attacked by Italian submarine Iride | Lost 4-1942 | ||

| I class destroyer | HMS Intrepid | Sunk 9-1943 | ||

| HMS Impulsive | Scrapped 1-1946 | |||

| Tribal class destroyer | HMS Mohawk | Sunk 4-1941 | ||

| HMS Maori | Sunk 2-1942 | |||

| HMS Afridi’s | Sunk 5-1940 | |||

| HMS Sikh | Sunk 9-1942 | |||

| V class destroyer | HMS Veteran | Sunk 9-1942 | ||

| HMS Vanoc | Scrapped 1945 | |||

| Arethusa-class light cruiser | HMS Penelope | Sunk 2-1944 | ||

| HMS Galatea | Sunk 12-1941 | |||

| HMS Orion | ||||

| Leander class light cruiser | HMS Leander | Scrapped 12-1949 | ||

| C-class light cruiser | HMS Coventry | Sunk 9-1942 | ||

| HMS Curlew | Sunk 5-1942 | |||

| D-class light cruiser | HMS Delhi * | Shelled by Canarius and bombed | Scrapped 1-1948 | |

| London Class heavy cruiser (13,000 tons) | HMS London | Scrapped 1-1950 | ||

| HMS Devonshire | Scrapped 6-1954 | |||

| HMS Sussex | Scrapped 2-1950 | |||

| Battleship Revenge-class (29,000 tons) | HMS Royal Oak | Bombed by Republicans 2-1937 | Sunk 10-1939 | |

| HMS Resolution | Scrapped 5-1948 | |||

| Battleship Renown class (31,000 tons) | HMS Repulse | Sunk 12-1941 | ||

| Battleship Queen Elizabeth class (33,000 tons) | HMS Queen Elizabeth | Scrapped 1948 | ||

| Battle Cruiser (45,200 tons) | HMS Hood | Sunk 5-1941 | ||

| Aircraft Carrier | HMS Glorious [+] | Sunk 6-1940 | ||

| French | Vauquelin class Destroyer | Maillé Brêzê. | Bombed | Blew up in port 4-1940 |

| Little data can be found | L’Adroit class Destroyer | l’Alcyon | Scrapped 11- 1952 | |

| German | Torpedo boat | – – | ||

| Corvette / Fast Torpedo boat (Type 24) | Leopard | Sunk 4-1940 | ||

| (Type 23) | Albatros | Attacked 5-1937 | Sunk 4-1940 | |

| K class light cruiser | Köln | Sunk 3- 1945 | ||

| Königsberg | Sunk 4-1940 | |||

| Karlsruhe | Sunk 4-1940 | |||

| Leipzig class light cruiser | Leipzig | Attacked by submarine | Disabled 12-1939 | |

| Pocket Battleship (12,000 tons) | Graf Spee | Sunk 12-1939 | ||

| Deutschland | Bombed 5-1937. 31 fatalities & 101 injured | Scuttled 5-1945 | ||

| SubmarineType IA | U 25 | Sunk 8-1940 | ||

| U26 | Scuttled7-1940 | |||

| Type VIIA | U 27 # | Sunk 9-1939 | ||

| U 28 | Sunk 3-1944 | |||

| U-31 | Sunk 3-1940 but refloated & sunk again 11-1940 | |||

| U 33 | Sunk 2-1940 | |||

| U-34 | Sank 8-1943 | |||

| Holland | Corvette van Nassau class | Johan Maurits van Nassau | Sunk 1940 | |

| Coastal defence Monitor | Hertog Hendrik | Sunk May 1940 | ||

| Cruiser | No data found | |||

| Submarine O-12 class | Hr. Ms. O 15 | Scrapped 1946 | ||

| Italy (91) | Destroyer | Melilla | ||

| 58 of the Sottomarini Legionari | SubmarineBrin class | Torricelli | Sunk 6-1940 | |

| Archimede class | General Mola | Scrapped 1959 | ||

| Minelayer | Barletta | Hit by bombs 6-1937 | Sunk | |

| Heavy Cruiser | Zara | Sunk 3-1941 | ||

| Spain / Gov’tRepublican | Cruiser | Libertad | Scrapped1/1970 | |

| Detailed list below | Battleship | Jaime 1 | Sunk 6-1937 | |

| Spain /Fascist nationalist (rebel) | E- Boats (German) | Falange | ||

| Detailed list below | Requeté | |||

| Cruiser | Almirante Cervera | Scrapped 9-1965. | ||

| Battleship | Espana | Sunk 4-1937 | ||

| Norway | No data found | |||

| United States | Clemson class destroyer | USS Kane | Bombed 8- 1936. No hits | Scrapped 6-1946 |

| (Squadron 40-T) | Destroyer | USS Badger | Scrapped 1946 | |

| USS Jacob Jones | Sunk 2-1942 | |||

| Light cruiser | USS Trenton | Scrapped 1946 | ||

| Battleship (27,500 tons) | USS Oklahoma | Sunk Dec 7th1941 | ||

| Portugal | No data found | |||

| Yugoslavia | No data found | |||

| Mexico | No data found | |||

| Argentina | Heavy cruiser (9,000 tones) | Veinticinco de Mayo | Scrapped 1951 | |

| * Some confusion arises over which HMS Delhi was involved in Spanish coastal policing. It was probably the first laid down in 1914 (scrapped Jan 1948). The second HMS Delhi launched in 1933 as HMS Achilles was transferred to New Zealand (HMNZS) and then transferred to the Royal Indian Navy as INS Delhi in 1948 (scrapped June 1978).# U-27 was sunk by HMS Forester.+ HMS Glorious was based at Oran to provide anti-submarine air cover over the Mediterranean | ||||

| NB. During WW2 the Allies lost some 1,383 warships to all causes, e.g. Royal Navy: 647 vessels. US Navy: 391, French Navy: 93, Dutch Navy:54. http://www.uboat.net/allies/warships/war_losses.html | ||||

–

Left: Argentinian cruiser Veinticinco de Mayo. She patrolled off Alicante from Aug to Dec 1936.

Left: Argentinian cruiser Veinticinco de Mayo. She patrolled off Alicante from Aug to Dec 1936.

The purpose of this number of warships was to offer a protective screen along Spain’s coastline. In the north protection was for refugee and humanitarian supply efforts and in the south it was legitimate trade and the supplying of munitions that became the attention of the non-interventionist force.

The notion of the freedom of navigation was uppermost in decisions reached. When, in August 1936, the Republicans suggested that they would blockade all ports in Nationalist hands, the French government showed it had a different agenda.

Since France did not recognise international belligerent status, the French protested that this “police measure” would undermine legitimate freedom of commerce. French warships were instructed not to allow merchant ships to be diverted by any blockade. Britain announced a similar policy and the result of ‘non-intervention’ was not protection but a policy of deterring third party trade with Spain which, for the Republic, amounted to a blockade in all but name.

Member nations passed laws restricting merchant traffic with Spain. Great Britain, for example, adopted the British Merchant Shipping Act, which banned carrying military supplies to either side.

By Nov 1936, and despite the Non-Intervention Committee’s regulations, the system descended into ineffectiveness. By late May 1937 the French ministry of marine noted that their efficacy was “illusory.” This was made all the more so when, following the attack on the Deutschland, the German delegation walkout out of the committee followed by the Italians.

This left them free to more openly provide technical advisors to Franco’s land forces and technical support to Nationalist ships.

Whereas the ‘control plan’ might have envisaged German and Italian warships patrolling in the Mediterranean with Britain and France the Atlantic seaboard, the entire burden of the ‘control plan’ fell on the shoulders of Britain and France.

By August 1937 submarine attacks on British, French, Russian, and Spanish shipping had markedly increased in the Mediterranean. The British response was to reinforce her Mediterranean squadron with orders to attack any submarine in the vicinity of a strike on a merchant ship.

Spain geographical position meant that whoever controlled Spain’s coastal waters could choke off world trade. This was critical at a time when the industrial world was only just taking tentative steps to emerge from the Great Depression (also known as “The Slump”). [3]

World trade had to pass close to Spain en route from Europe (and the US) to the Mediterranean and then via the Suez Canal to the Far East.

European trade to South African and South American bound trade also had to pass close to the Spanish coast line.

Were it not for the naval fortress of Gibraltar counteracting this threat the possibility was that half the world’s trade could be held to ransom (comparable to Somali pirates of 2009 – but by forces far better equipped, funded and organised than the Somalis).

From the outset both regimes in Spain sought international recognition to be the true voice of Spain and both realised that control of the seaways would ultimately intimidate the great powers into diplomatic recognition and/or acquiescence.

The belligerent parties could not have been more ideologically opposed. The 1930s was the decade that saw politics uniquely polarised between fascism and communism, especially in Europe.

The imposition of a ‘3 mile exclusion zone’ by the Fascist forces under Franco was the excuse, some would say the cause, for many of the ship sinkings, seizures and cargo confiscations. The intent by one side to enforce the exclusion zone and the other sides attempt to invalidate it lay at the heart of subsequent deadly skirmishes at sea as the regimes competed for superiority and international to recognition.[4] It also meant that neutral shipping was caught up in the competing struggle.

The leading European nations with the exception of Italy and Germany decided not to become involved in Spain’s civil war. However, ships of all nations participated in the early months in evacuating foreign national from Spain with for instance German ships evacuating Americans fleeing and American ships assisting many other nations citizen. [5] It was only later that Italian and German warships took a pro-active role on behalf of Franco’s fascist forces.

The humanitarian side of the Spanish Civil War began positively with multi-national co-operation and shared evacuation of foreign nationals by neutral powers.

It ended, infamously, with the evacuation under gunfire and dive bombing attacks of children in converted hospital ships.

attacks of children in converted hospital ships.

Left: ‘Taking on board refugees’. The ship is thought to be the L’Alcyon, a French L’Adroit class destroyer.

When Franco began his overthrow of the Spanish government, on July 17th 1936, those nations that had naval forces in Spanish waters or were close by (e.g. France, Germany, Russia, Great Britain, Italy and the United States), combined to assist third parties and neutrals and foreign nationals.

By the time a U.S.merchant ship reached Barcelona several days later most Americans had already been evacuated aboard other nations’ ships.

“In November, the Germans asked the British to assist them in evacuating their citizens from southern Spain. This pattern continued through the war.” – International Naval Cooperation During the Spanish Civil War.

By July 1937 the Royal Navy had rescued over 27,000 people. The U.S. Navy evacuated over 1,500 people, of whom only 633 were American citizens. The German navy evacuated 9,300 in July and August 1936, half were nationals from third countries. The combined navies removed 50,000 foreigners and 10,000 Spaniards by the end of 1936. (NB. former MP, Michael Portillo’s father fled from Franco’s forces at this time).

The first few months were the honeymoon period of joint operations and co-operation. Intelligence and routes of communication were pooled. For instance, the first messages sent to the US State Department by the consul at Barcelona calling for the evacuation the U.S. citizens, went via the Royal Navy. [6] The small US destroyer flotilla (Squadron 40-T) immediately returned to its base at Villefranche, south of France, as soon as all American nationals had been collected from Spain in the autumn of 1936.

By the end of the year (Dec 1936) the warships of the original nations had been joined, if temporarily, by elements from Argentina, Mexico, Portugal, and Yugoslavia – followed by Holland and Norway when their merchant shipping became embroiled.

The end of the honeymoon was signalled in the Autumn of 1936 by German and Italian recognition of the Franco regime and confirmed by Italian warships bombarding Spanish harbours in Jan and Feb 1937. Throughout 1937 both Germany and Italy stepped up their covert and overt support of Franco.

Refugees

The ‘blitzing’ of Guernica (northern Spain), a town near Bilbao and of no military significance, by the Luftwaffe and its bombardment by Fascist artillery, triggered a mass evacuation of children to avoid further mass civilian causalities.

Agencies in England organised the hiring of the S.S.Habana, formerly a hospital ship, to evacuate children from the Bilbao area. At 10,551 tons the Habana was the second biggest ship of the Cia Transatlantica fleet.

Agencies in England organised the hiring of the S.S.Habana, formerly a hospital ship, to evacuate children from the Bilbao area. At 10,551 tons the Habana was the second biggest ship of the Cia Transatlantica fleet.

In May 1937 some 3,840 Spanish Basque children crammed aboard the SS Habana – all had one suitcase and a label listing their name tied with string to their lapel. The children came with 80 teachers, 120 auxiliaries and 15 catholic priests.

Left: The crowded decks of the S.S. Habana, July 1937.

Captain Ricardo Fernandez, Master of the Habana, had been responsible for the evacuation of two previous shiploads of refugees to France. On the eve of departure the S.S. Habana came under aerial attack but all the bombs missed the ship.

More information on the Habana and its child refugees can be found at “Anna Freud Part 2” (http://robertwhiston.wordpress.com/tag/anna-freud/).

Prior to the fall of Bilbao other refugee ships had come under indiscriminate attacks from ship launched torpedoes and both high altitude bombers and dive bombers. This total disregard for international maritime law led (in 1937) to nine ships, all British, and all carrying refugees from Santander, receiving naval protection on the high seas after the fall of Bilbao.

The total number of refugees carried by these ships is estimated at 16,091. [7] Some 4,000 came to Britain. Other ships took other Basque children to Mexico, Belgium, France, and the Soviet Union. Only later was it discovered that children who arrived in Russia would never be allowed to return to Spain.

Blockade Runners

No commentary of this period would be complete without some mention of the brave individuals who defied governments to do ‘the right thing’ and brought food to a starving civilian population (see ”9. The Blockade Runners and ‘Potato Jones” http://www.terrynorm.ic24.net/spanish%20civil%20war.htm#9).

The popular American journal “Time” covered this aspect of the conflict under “Foreign News: Welsh Basques” (May. 03, 1937); quote, “More than one-tenth of the cargo was paid for by David Lloyd George [the former British Prime minister] . . .” The magazine also reports that half-a-dozen freighters also ran the blockade to Bilbao. (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,931579,00.html#ixzz0hPgVH1qd)

“Time” epitomises American disengagement and disinterent in the human suffering by describing those who did try to help as mere “sentimentalists”.

David ‘Potato’ Jones was one of three Welsh sea-captains who ran goods – and guns – to northern Spain for the opponents of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. All three were called David Jones – nicknamed “Potato”, “Corn Cob” and “Ham ‘n’ Chips” Jones to distinguish them.

To this day they are remembered by those that lived through the Bilbao of 1937.

The extent of the attacks on merchant men and interference with neutral shipping is far higher than most modern accounts of the era indicate. The extent can be gauged from the table below showing just some of the better documented instances of seizure and confiscation of merchantmen.

Contraventions of international law occurred not solely within coastal exclusion zones proclaimed by both sides but, as in the case of the British S.S. Alcira, 20 miles off shore. She was bombed and sunk by Nationalist sea planes on February 4th 1938.

To give some perspective to the conflict, Italian pilots reportedly flew 135,265 hours during the war, and took part in 5,318 air raids.

As early as July 27, 1936 the first squadron of Italian airplanes arrived in Spain. The fact that they were sent by the Italian dictator Mussolini indicates a degree of prior knowledge and planning.

Italian reportedly attacked or hit 224 Republican and other ships. Italian pilots also reportedly engaged in 266 aerial dogfights claiming 903 Republican and allied planes shot down. However, this figure should not be relied upon; the size of Spain’s Republican Air Force was, in 1936, put at only 488 aircraft.

The question of ‘belligerent rights’, such as the authority to institute a blockade or stop ships on the high seas, remained a constant thorn and frequently provoked naval responses.

Republican warships attempted from August 1936 to blockade all the ports used by Franco’s rebel army while navy elements loyal to Franco tried to blockade ports held by Republican forces.

The result was that any merchant ship attempting to enter a port would be warned off or attacked by one side and encouraged or given escort by the other.

From 1937 to 1939 the Armed Merchantmen, Mar Negro, together with the Italian built destroyer Melilla enforced such blockades outside various port, e.g. from Valencia on the Atlantic to Palma in the Mediterranean.

Right: the Nationalist light cruiser ‘Almirante Cervera’

Right: the Nationalist light cruiser ‘Almirante Cervera’

By 1939 Franco felt confident in the effectiveness of his navy to back up his army’s sucesses by declaring a 3 mile exclusion zone. It was this 3 mile limit that the British freighter Stangate, violated and as a consequence was captured. The S.S. MacGregor with 2,000 refugees on board was shelled by Franco’s warship, the Almirante Cervera, as she left Santander in July1937. [8]

From 1937 to 1939 the Armed Merchantmen, Mar Negro, together with the Italian built destroyer Melilla enforced such blockades outside various port, e.g. from Valencia on the Atlantic to Palma in the Mediterranean.

|

Merchantmen and neutral shipping incidents – by regime responsible 1936 -1939 (not a complete list) |

||

| Merchant ship | Attacked by:- | |

| Franco –Nationalist | Republican Government | |

| British S.S. Habana Refugee Ship – UK | Attacked by bombs Bilbao 1937 | |

| S.S. Molton Refugee ship– UK | Rescued but later captured 1937 | |

| S.S. Gordonia – RefugeeShip – UK | Rescued by HMS Resolution ’37 | |

| S.S. Seven Seas Spray – food ship | Stopped 1937 | |

| S.S. Marie Llewellyn – 1937 food ship, 1939 Refugee ship | HMS Hood warns off Rebel cruiser | |

| S.S. Alcira | Bombed & Sunk 2/1938 | |

| S.S. Burlington | Captured 1937 | |

| S.S. Endymion | Torpedoed & Sunk 2/1938 | |

| S.S. Thorpehall | Stopped | |

| S.S. Latymer | Stopped | |

| S.S. Stanhope, | Stopped | |

| S.S. Stanbrook * Refugee & food ship | Shelled at sea 4-1937 | |

| S.S. Stangate | Seized by Nationalists 1939 | |

| S.S. Stanray | Attacked 6/1937 | |

| S.S. Stanland | Stopped | |

| S.S. Stangrove (550 tons) | Seized by Nationalists | |

| S.S. Dellwyn | Captured | |

| S.S. Candleston Castle, | Captured | |

| Llandovery Castle British liner | Hit & badly damaged by mine 2-1937 | |

| S.S. Dover Abbey | Captured | |

| S.S. Yorkbrook | Captured | |

| S.S. Sarastone | Attacked | |

| S.S. Hillfern | ||

| S.S. Bramhill | Shelled in port | |

| S.S. Hamsterley * Food convoy | Shelled at sea 4-1937 | |

| S.S. MacGregor * Refugee Ship – UK | Shelled at sea 4-1937 & 7-1937 | |

| S.S. Pomaron | Seized by2-1938 | |

| French merchantmen Cens | Captured | |

| German freighter Kamerun | Stopped 1936 | |

| Palos | Captured | |

| Spanish Republic Cabo Palos | Sunk 7-1937 | |

| Marqués deComillas | Seized by Nationalists | |

| Ciudad de Barcelona | Sunk 5-1937 | |

| Sil | Captured 1938 | |

| Río Miera. | Captured 1938 | |

| S.S.Cantabria | Sunk 11-1938 | |

| Josiña | Interned 1938 | |

| Guernica | Interned 1938 | |

| Holland merchantmen x 18 | Cargo confiscated. | |

| S.S. Hannah | Torpedoed & sunk 1938 | |

| SS. Parklane | Aerial attack | |

| Mexico merchantmenMar Negro | Captured | |

| Danmark merchantmenx 26 | Cargo confiscated. | |

| Norway merchantmen x 30 | Cargo confiscated. | |

| Greek Victoria | Captured 1938 | |

| Panamanian | ||

| USSR Katayama | Captured 1938 | |

| Potishev | Captured | |

| Konsomo | Sunk 12-1936 | |

| Blago’ev | Torpedoed 9-1937 | |

| Timiryavez | Torpedoed 8-1939 | |

| Smidovich | Captured | |

–

Right: the Republican destroyer Ciscar

The vigour with which the two competing regimes managed their war fleet is most marked. The rebels (Fascist) were out-numbered in terms of quantity of ships but were far more audacious in their use of resources. the number of ships stopped, seized or sunk compared with the Republican naval forces tells its on story.

The vitality, resourcefulness and daring of the Fascist ship commanders brought them into conflict with much larger and more modern warships of the internal protection fleet. The rewards for this level of enterprise greatly out shone that of the Republican Navy.

For instance, merchantmen like the steamer S S Gordonia had to be rescued by the 29,000 ton battleship HMS Resolution when a Spanish nationalist warship of a mere 7,500 tons attempted to capture her off Santander (northern Spain). ‘The Hood’ had to steam a significant way north to Bilbao with a destoyer escort in 1937, to defend the tramp streamer Marie Llewellyn from a Nati0nalist heavy cruiser blocking entry to the port (probably the Canarias).

Other merchantmen like S S Molton were helped a first time but could not be helped a second time, even with HMS Resolution in close attendance. The Molton was eventually captured by the Spanish rebel cruiser Almirante Cervera when she later tried to enter Santander harbour.

The ports of Bilbao, Santurce and Santander were the principal avenues of escape for refugees along the northern coast and as a result were the setting for several notable engagements.

Merchant shipping losses were high because of the direct involvement of Italy under their dictator Mussolini. In all, Italy sent and or made available to Franco approx. 91 Italian warships and submarines. They sank it is estimated some 72,800 tons of shipping loosing 38 sailors in the process.

After Dec 1936 Germany appears to have been more ready to invoke gunboat diplomacy to protect her interests in Spain. Her navy pursued a pro-active approach. It seized, for example, two Republican vessels at one point and turned them over to Nationalist forces as part of the pressure applied ton the Republican side to release the seized German merchant ship Palos.

For their involvement on behalf of one of the belligerent parties, Italy and Germany presented Franco with a bill for their support. In the case of Italy it was for £80,000,000 or approx $400,000,000 at 1939 prices. This perhaps the best value-for-money as Italy was generous in its supply of hardware.

Germany’s invoice was for approximately £43,000,000 ($215,000,000) in 1939 prices. [9] Approx. 22% related to supplies directly delivery of to Spain, and about 63% was spent on hiring the Condor legion of the Luftwaffe.

Russia, which was the Republic’s main arms supplier, was paid in what has since become known as Moscow Gold. The central bank in Madrid held the world’s 4th largest gold reserves in 1936 (estimated at US$750 million). A large proportion of this gold bullion was physically shipped to Russia to avoid it falling into fascist hands (and probably because Stalin preferred gold to paper money). Whether the Republic actually got full value for it millions in gold is still open to speculation. [10]

One suspects that in a command economy such as the USSR, tanks and rifles cost the Kremlin absolutely nothing and were only given a nominal value. If so, some observers speculate the gold bullion could have funded Soviet activities including fueling divisions and social unrest overseas during the Cold War years.

The unlikely role that gold bullion played for both Stalin and Hitler in the Spanish Civil War and World War II are briefly dealt with in “9. How pivotal was Gold ?”

Compared with the tanks, ships and planes provided, loaned and hired out by both Germany and Italy, Russia’s effort was paltry. She did not provide the Republic with cruiser, destroyers and submarines as Italy did. Both Italy and Germany provided military personal, 50,000 and 10,000 respectively.

The German military attached estimated that Soviet and Comintern aid amounted to supplying 242 Aircraft, 703 pieces of artillery, 731 tanks, 1,386 trucks, 300 armored cars 15,000 heavy machine guns, and 500,000 rifles.

The German military attached estimated that Soviet and Comintern aid amounted to supplying 242 Aircraft, 703 pieces of artillery, 731 tanks, 1,386 trucks, 300 armored cars 15,000 heavy machine guns, and 500,000 rifles. This has to be put into context of Nationalist and German claims that Britain was both supplying the Republicans with ammunition through Bilbao and passing on intelligence about Russian shipments to the Nationalists – a blatant attempt to undermine Britain’s neutrality.

These supposed amounts of munitions must be viewed as an over-estimate as it would probably form part of German propaganda and misinformation. Battlefield reports repeatedly underline how the Republican forces were continually out-manoeuvred, out-numbered and out-gunned, e.g. the fighting around Santander, August 1937.

In fact, the 2nd largest supplier appears to have been Poland which was one of the few countries willing to sell arms in spite of an embargo, others included France, USA, Czechoslovakia and Mexico. Modern research conducted after the collapse of the Iron Curtain shows that Poland was second after the USSR in selling arms to the Republic. In the autumn of 1936 Poland was the only nation to offer arms to the Republic in any quantity.

Compared to other European nations Spain had neglected her navy. It was not only small but generally out-dated with her principle capital warships being dreadnoughts dating from the First World War (see Jaime I and España, below).

She did, however, embark on a modernisation programme in the late 1920s and early 1930s. These took the form of smaller, modern craft, i.e. cruisers and destroyers which were largely built to British designs, e.g. Canarias, (10,000 tons, 32 knots), Almirante Cervera and Libertad (Cervera class, 7,000 tons, 6” guns and 33 knots).

Other than these ‘jewels’ of the fleet, Spanish warships were an ad hoc mixture of ill fitting vessels. For instance, the fleet included elderly mine layers capable of 15 knots and the Méndez Núñez, a destroyer, laid down in 1915 and launched in the early 1920s. Her top speed of 25 knots meant she could not act as escort for, say, the Canarias.

The advantage the Republican side had was in the number of destroyers at its disposal but this was never made to count. The rebel (fascist) side with far fewer ships nonetheless used them to far more effect. The one advantage the rebel (fascist) had over the republic was in terms of heavy cruisers (10,000 tons and 33 knots). There was nothing on the Republican side to match their 8” guns.

Both the Canarias class and Cervera class were comparable to any cruisers in the International Force.

The under-use of a superiority in numbers by the Republican side is again demonstrated in terms of submarines available. Official lists indicate Spain had 12 submarines yet no account can be found of their use during the Civil War. What can be found is a chronicle attacks and sinkings by two Italian submarines used by the Fascist side (for submarines General Mola and Torcellini, see Sect 7. ‘Submarines’ below).

| Spanish Naval Forces (1936 – 1939) | ||

|

Franco – Nationalist |

Government Republican |

|

| Type |

Quantity / name |

Quantity / name |

| Battleships |

1 |

1 |

| Heavy Cruisers |

(2*) |

– – |

| Light Cruisers |

1(1*) |

3 |

| Destroyers |

1(4**) |

14(2*) |

| Torpedo boats | 5 Falange (sunk 6-1937), Requeté, Javier Quiroga (sunk 5-1937) |

7 |

| Auxilaries / Sloops (rated asGunboats but today would be described as Corvettes) | 4 (1*) Italian auxiliary Barletta (aka Rio) bombed 5-1937, hit, 6 killed. Italian Adriatico (aka Lago). Vicente Puchol |

1 Laya (sunk by aircraft. 6-1938) |

| Minelayers | (3*) Vulcano, Jupiter, Marte, Neptuno, Antonio Lázaro |

27 * |

| Coast Guard ships (Corvette) | 4 Eduarto Dato (sunk 8-1936) |

5 |

| Armed trawlers | – – | Bizkaya, Donostia Gipuzkoa, Nabarra, Goizeko-Izarra * Gazteiz |

| Auxiliary Motor Boats | – – |

Josuren Ama, Angel de la Guarda, San Isidro, Nazareno, San Ignacio De Loyola |

| Submarines |

(2**) |

12 |

| Men | 7,000 | 13,000 |

| Source: The Armada Española 1936-39 and others, e.g. Wikipedia. http://www.kbismarck.com/mgl/spanishcivwar.htm.* For complete list see http://www.gudontzidia.eu/en/base-datos-buques.php | ||

–

Lepanto was one of the more successful Republican destroyers. She survived a mutiny by her officers who wanted to switch to the Rebel (nationalist) side. At the battle of Cabo de Palos (March 1938) she successfully torpedoed and sank the nationalist cruiser Baleares.

The Lepanto was escorting the light cruisers Libertad and the Mendez Nunez. While the cruisers on both sides exchanged fire in darkness (02.00 am), two Republican destroyers launched torpedoes.

One or two torpedoes from the Lepanto hit the heavy cruiser Baleares and her forward magazine blew up . Only her stern half remained afloat. Of her crew of 765 two British destroyers, HMS Boreas and HMS Kempenfel found only 372 to rescue.

When a Rebel (nationalist) convoy including a troopship and escorted only by the gunboat (Corvette) Eduarto Dato was intercepted by the destroyer Alcalá Galiano the latter was driven off the by gunfire from the Dato and patrolling aircraft (the Alcalá Galiano, launched in 1931, was scrapped in 1957).

The website “World Naval Ships Forum” gives a brief history of most of the vessels in the Spanish fleet of that time. http://www.worldnavalships.com/forums/showthread.php?p=97055

One would have expected torpedo boats to have played a far more decisive role in coastal combat than they appear to have done. Their use in World War II in the form of German E-Boats and British MTB boats demonstrated how they could wreak havoc, menace merchantmen and generally pose a threat to and tie up larger naval fleet vessels.

The diversity of smaller craft is exemplified by the 1,266 ton yacht Giozeka Isarra * (Morning Star) (later to become the 4th HMS Warrior). In 1920 she was purchased by Sir Ramon De La Sota, of Bilbao, and during the Spanish Civil War she was used by the Basque Government to carry refugees and wounded Spanish children between Spanish and French Biscay ports. [11]

The disposition of warships shown in the table below takes no account of these small but effective craft.

| Major Warship Strengths (Sept 1939) | |||||

| Navies | Royal Navy | French Navy | German Navy | ||

| Warship types | Home waters (a) | Atlantic (b) | Atlantic and Channel | European waters | Atlantic station |

| Battleships |

9 |

– | 2 | 3 |

2(c) |

| Carriers |

4 |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

| Cruisers |

21 |

14 |

3 |

7 |

– |

| Destroyers |

82 |

13 |

20 |

22 |

– |

| Submarines |

21 |

4 |

– |

41 |

16 |

| Totals |

137 |

31 |

26 |

73 |

18 |

|

plus escorts |

– |

– |

plus torpedo boats |

– |

|

–

Armed merchantmen

The role for maritime engagements by this type of converted ships into that of a warship for use against unarmed ships has a long pedigree. They were used by many countries in the First World War and were sometimes known as ‘Q ships’ in as much as not revealing their armaments to a merchantman until it was too late (see Kormoran and HMAS Sydney, Nov 1941).

Germany perhaps excelled at this, e.g. the German armed merchantman Komet,and took the process a step further by building for World War II several ‘pocket battleships’ specifically designed as commerce raiders and not for ‘fleet engagements’

These ships, the Admiral Scheer, Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee were built in 1936 to take on any pursuing cruiser or destroyer of the time yet were fast enough, at 28 knots, to out-pace any battle cruiser. The belief at the time was that they were designed to out-run what they could not out-gun was short-lived with the arrival from 1939 onwards of the King George V class battleships, e.g. HMS Howe, HMS Anson and HMS Prince of Wales each capable of 28 – 30 knots.

The pocket battleships were frequent visitors to Spanish waters and active participants on the side of Franco. Their main armaments of 11” guns aboard a cruiser sized hull (12,000 tons) gave rise to much naval interest. When the Deutschland was forced to put into Gibraltar for repairs and bury her dead after being attacked and damaged from the air, naval intelligence services were able to gain a better understanding of her capabilities. The Deutschland was renamed Lützow (Nov 1939), probably to avoid the political embarrassment of having a ship named Deutschland captured or sunk. The attack and the damage casued to the Deutschland was far more significant than was realised at the time (see Addendum at the foot of this article). Also far more significant were the elements of German navel forces deployed in the Mediterranean and I am grateful to Ignacio Recalde (Spain) for highlighting this.

The Barletta was just such such an armed merchantman. Designed as a merchant man she was converted into an ‘auxiliary’ or armed merchantman. After an effective series of engagements she was attacked while at anchor in Palma by Republican bombers. The decision was taken to disarm her and use her instead as a supply ship. Later, when the Spanish Civil War ended the Barletta was returned to Italy. The Italian ship Adriatico which was also used to assist Franco’s war effort was similarly disarmed and used as a supply ship by Franco’s forces before being returned to Italy. She was later sunk in World War II by HMS Aurora on Dec 1st 1941.

The Vicente Puchol was initially deployed as an improvised minelayer but was later converted to an auxiliary cruiser. The Antonio Lázaro was another improvised minelayer, which was also later converted into an auxiliary cruiser, i.e. an armed merchantman.

Working in tandem with the minelayer Jupiter, the Ciudad de Palma which the Italians had converted in 1936 from a merchant ship into a warship captured of the British cargo ship Candlestone Castle (17th July 1937).

One of the most extraordinary things to discover is that far from operating against merchant shipping in coastal waters, Nationalist (Franco’s) warships operated in shipping lanes as far away as the eastern Mediterranean intercepting supplies form Russia and as far north as Norway and the North Sea.

The Ciudad de Valencia which also used the alias ‘Nadir’ was on active operations in the North Sea. Off the coast of Norfolk (eastern England) she sank the Republican merchantman. S.S. Cantabria (Nov 2nd 1938). Off the coast of Norway she found and engaged the Republican steamers Josiña and Guernica (Nov 19th 1938). Both fled to safer waters with the Guernica choosing Swedish waters where she promptly ran aground. The Josiña fared no better she reached Kristiansand but was interned and remained there until 1939. [12]

The Ciudad de Valencia activity was made possible by the support and joint working with the Ciudad de Alicante. She supported the Ciudad de Valencia in the North Sea, where she played a secondary role in the capture of the Republican steamers Sil and Río Miera. Both the Ciudad de Alicante and Ciudad de Valencia used the German port of Linden as a re-supply base.

When not ensuring safe conduct for unarmed merchantmen and protecting if stopped, the International Force found itself picking up the pieces and survivors of bloody skirmishes between the two Spanish fleets (see Lepanto citation above).

At the start of the Civil War, the underwater threat of submarines, usually Italian with a Spanish officer posted aboard, posed a serious risk to ships of the international force. HMS Havock was attacked by a submarine and a Republican submarine attacked the German cruiser Leipzig – which provoked retaliation from Germany.

At the time and despite protestations, Italy was suspected of having a major hand in these events. Many years later it was revealed just how extensive was Italy’s involvement. For example we now know that in 1936 the Italian submarine Torcellini, while still under the Italian flag, torpedoed the Republican cruiser Miguael de Cervantes. The Torcellini was later nominally transferred to the Spanish fleet and renamed General Sanjurio. As such she sank the transport Ciudad de Barcelona (30th May 1937) and the British steamer Endymion (21st Jan 1938). ). Reportedly 58 submarines from the Sottomarini Legionari (part of the Italian Navy, Regia Marina) operated on behalf of the Nationalists in the Mediterranean (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kriegsmarine#Spanish_Civil_War).

Of the four Archimede class submarines (launched circa 1933) only two, the Archimede and the Torcellini saw action in the Spanish Civil War. [13] By the late summer of 1936 the Archimede was already operating covertly in Spanish waters. In April 1937 she was nominally transferred to Franco’s Navy and as the General Mola sank the Republican transport ship Cabo Palos (26th July 1937) and the Dutch freighter Hanna (2nd Jan 1938). When the submarines C-3 and C-5 were sunk, the Nationalist claimed they had captured them and were using them – when in fact the two submarines were the Torcellini and Archimede.

In the table above (i.e. “Spanish Naval Forces 1936 – 1939”), a total of 14 submarines are listed. Two as mentioned above were in fact Italian and 12 of which were at the disposal of the Republic. Theses 12 consisted of a fleet of six B-Class submarines (launched in 1922) and six C class launched in 1929. Two B-Class submarines were sunk in 1936 (B-6 and B-5 though the date for B-5 is put variously as Sept and Oct). The rest were scuttled in April 1939 except B-2 which was scrapped only in 1948. [14] (See table below).

|

Spanish B-Class submarines A picture is available of B1, B2, B4 and B5 at Santander Harbour c.1930 |

|||

| B 1 | Cartagena | 1921 | Scuttled April 1939 |

| B 2 | Cartagena | 1922 | Broken Up 1948 |

| B 3 | Cartagena | 1922 | Scuttled April 1939 |

| B 4 | Cartagena | 1922 | Scuttled April 1939 |

| B 5 | Cartagena | 1923 | Sunk 12th Oct 1936 |

| B 6 | Cartagena | 1923 | Sunk 19th Sept 1936 |

–

The chronicle of the six C-Class submarines is not so clear. Only C-3 has a clear wartime log.

C-1, together with C-3, C-4, C-5, C-6 and B-6 formed a patrolling flotilla in the Straits of Gibraltar in July 1936. However, internal conflict – probably political in origin (and which was not uncommon in Republican circles as Socialists vied with Communists for dominance) led to the arrest and imprisonment of the majority of the flotilla’s senior officers.

The fate of the C-Class submarines is less clear but C-4 sank with all hands after colliding with the destroyer Lapanto during manoeuvres in June 1946 (the Lepanto was scrapped in 1957). [15] C-4 had some success; she torpedoed the elderly battleship Espana but the torpedo failed to detonate. C-6 is believed to have been scuttled after suffering a severe aerial attack in Oct 1937 (see http://www.orwell.ru/a_life/Spanish_War/english/e_events).

The response to all this submarine activity was the Nyon Agreement of Sept 1937. This obliged nations to provide up to 50 destroyers for anti-submarine patrols duty. For Britain it meant it had to commit three-fifths of its entire destroyer fleet and so had to withdraw some ships from the Non-intervention Committee patrols in Spanish waters.

With 27 destroyers constantly ‘on station’ submarine attacks quickly abated.

In January 1938 the Royal Navy decided to reduce patrols in light of the absence of submarine attacks. Not long afterwards rebel fascist, i.e. Nationalist, submarines went back to sea and strikes on shipping resumed.

The role of submarines in World War II was markedly more aggressive. In the lull between the end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of World War II in excess of 30 German U-boats slipped passed Gibraltar and into the Mediterranean. These craft together with Italian submarines sank many ships in convoys destined for Malta and the North African campaign. Additionally, the Mediterranean was the theatre of operation where the Royal Navy lost most surface warships. However, none of the German U-boats made it out of the Mediterranean. Compared to the deep and murky grey waters of the Atlantic the two continental shelves make for shallow waters along North Africa, Italy, the Aegean, Malta, Sicily and Greek island. No depth and crystal clear waters made submarines vulnerable to air attack.(http://www.divinglore.com/Genesis/Mediterranean%20Depth%20Chart.html).

At 42,000 tons HMS Hood was indisputably the fastest and most heavily armed battleship of her era. Her 15″ shells could travel over 17 miles but fatally she had only 3″ of armoured decking.

HMS Hood was in overall command of British naval vessels and responsible for co-ordinating ships of other navys.

Right: HMS Royal Oak

Battle cruisers, with their 15″ guns, provided the necessary intimidation to make destroyer escort screens effective around the three coast lines of Spain. The potential of engaging with such capital ships as HMS Royal Oak, HMS Resolution, and HMS Queen Elizabeth, (29,000 tons) proved enough of a deterrent in most instances ensure neutrality.

The refugee ship the S.S. Habana at the dock side. She was one of several refugee ships that came under attack when leaving harbour.

The refugee ship the S.S. Habana at the dock side. She was one of several refugee ships that came under attack when leaving harbour.

Left: S.S. Habana

The scourge of merchant shipping was the Canarias class and Cervera class cruiser in the hands of the Nationalists.

Right: the Canarias

The most notable skirmishes involve or mention the 10,000 ton Canarias. Among ships of her time she is distinctive in have her funnels blended into one large stack.

The Almirante Cervera was a light crusier with an equally good record for audaciousness.

Left: the Admirante Cervera, 7,000 tons

Left: the Admirante Cervera, 7,000 tons

Graf Spee, and her sister ships, the Admiral Scheer, and Deutschland actively supported Franco and shelled Republican positions.

Below: Admiral Graf Spee, 12,000 tons and 610 ft long (see Addendum A below).

They were accompanied and supported by other warships of the Kriegsmarine, in the form of Type 23 and 24 Flottentorpedoboot, or fleet torpedo boats.

The Germans called them torpedo boats but at over 1,000 tons and more than 300 feet long, they were more comparable to corvettes or destroyers in size than MTBs. Nor should they be confused with the slightly larger (at 100 tons), Schnellboote, aka E-Boats.

Below: Albatros, Type 23

Despite their lack of speed and armaments the small group of Spanish Jupiter class minelayers proved more than a match for Republican destoyers.

Gunfire from the Jupiter straddeld HMS Foxhound as she engaged the Republican destroyer Cicar (10th Aug 1937)

Germany made available U-boats and Schnellboots (S-boats, i.e. “fast boat”). The latter would come to be generally termed E-boats during World War II. Both U-boats and E-boats were very effective at harrassng coastal shipping and bottling-up ports.

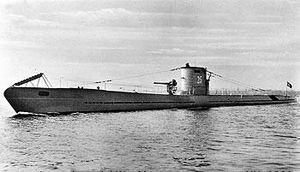

Right: U-34

U-34 was a Type VIIA. Launched in 1936, she sank the Spanish submarine C-3 on 12 Dec, 1936. U 34 sank after a collision on 5 August, 1943.

Left: Requeté, a Spanish rebel E-boat

The lineage from the Requeté to the E-boats of WW2 is clear with torpedo tubes flaired into a larger bow. At 100 tons S-boats were approximately twice as large as their British and American motor torpedo boat (MTB) counterparts. They were better suited for the open sea, and had a substantially longer range, at approximately 700 nautical miles.

Steel hulled and diesel powered, they were far less flammable than MTBs or PT boats.

Right: German E-Boat pictured in Felixstowe harbour, May 1945, after Germany’s surrender.

Armed merchantman or Auxillaries figured prominerntly in the Spanish Civil War. Both the Mar Negro (6,600 tons), and her sister ship Mar Cantábrico were seized by Franco’s Nationalists and converted into ‘auxilary cruisers’.

Left: Mar Negro, showing her recently installed turrets

Left: Mar Negro, showing her recently installed turrets

Below: HMS Sussex, 13,000 tons, in her wartime anti- U-boat ‘Dazzle’ camouflage

Her sister ship, HMS Devonshire, played an important role in bringing the two sides together and restoring peace to Minorca in Feb 1939. The island sided with the Republicans during the civil war. As a result the Italian Air Force subjected the island to an aerial bombing campaign. After the Governor signed the treaty for the surrender of Minorca it was agreed that HMS Devonshire should evacuated 470 political refugees to Marseilles. Given Franco’s human rights record, they would have been executed or sentenced to long terms of hard labour had they stayed.

Right: Leipzig, the Republican submarine attack on the cruiser allowed Hitler to cancel further international co-operation.

During the inter-war years America had an aversion to what it termed ‘foreign entanglements’. America played no part in the Non-Intervention fleet and did not participate in efforts to confine the conflict. Domestic politics, both Democrat and Republican, demanded a policy of isolationism and no overseas involvements.

America continued to fulfil its muniti0ns contracts with the beligerents and restricted its role to diverting the elderly USS Oklahoma, already in European waters, to pick up nationals from Bilbao in August 1936.

Above: USS Oklahoma, 27,500 tons, launched 1914

Addendum A

In the 1930s Germany’s pocket battleships presented the confident and implacable face of a resurgent German navy. The ships were thoroughly modern in having diesel engines, a wielded and not riveted hull (which cut down weight and drag) and were, with a 3½ inch (80 mm) armored hull side-belt, generally considered very well engineered

It was only during repairs at Montevideo, after the Battle of the River Plate, that a design weakness of fatal flaw proportions revealed itself. The Graf Spee was peppered with 6” shells from HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles piercing her hull and super structure but she was more or less intact despite the loss of some functionality. However, it was the 8” shells from HMS Exeter that sealed her fate and ultimately that of her class.

It is clear from the operational log of the Lützow (formerly the Deutschland), that during its time in Norwegian waters (1940), her officers were fully aware of this design flaw and for this reason her sorties were limited and her engagements with the enemy always brief (see Postscript below and Addendum B).

All warships use what is called burner oil as fuel in their boilers. Sometimes they are known as fuel oils bunker A, B, or C, or residual fuel oil (referred to as RFO). These fuel oils can be light, or heavy, or contain special additives.

The Graf Spee and her sister ships had a system that required pumps to cleanse the oil prior to its use. One, 8” shell from HMS Exeter had pierced into the engine room and had wrecked her oil pumps. It was not hull or structural damage that brought her to her knees but the demolition of her cleansing pumps which also desalinated water for the crew. The Graf Spee was effectively dead in the water with no suitable fuel to burn. A warship’s boiler room produces high pressure steam which is used to move and clean raw fuel from the storage bunkers into ‘day tanks’, i.e. fuel tanks ready for immediate use.

Crude oil while quite functional as a boiler fuel nonetheless carries a hazard connected with the lighter hydrocarbon elements not having been distilled out. In this unrefined form highly flammable vapours can form in the ship’s fuel tanks. Should a shell penetrate the compartment or venting pipes during battle this could result in a fuel tank explosion.

This danger this posed was not lost on Capt Langsdorff and his Chief Engineer. The vulnerability of the icons of the Kriegsmarine had to be kept secret – not just from the Allies but from rivals in Germany anxious to have naval spending diverted to their Army or Airforce projects.

For all their conceptual brilliance these pocket battleships had comparatively thin deck armour – a captured ship would have revealed this. With no possibility of continuing to fight outside Montevideo or of having enough fuel to outrun her pursuers or to seek deeper waters, her fate was sealed – scuttling was the only option.

The attack on the Deutschland in 1937 could have been brushed aside as simply unfortunate but not the damage experienced by the Graf Spee in Dec 1939.

Postcript:

Some naval sources maintain that the Nürnberg was the only ship in her class, e.g. ‘worldnavalships.com’, whereas other sources include her in the Leipzig class – itself an improved K class cruiser. Although similar there were differences; The Leipzig displaced 8,380 tons but the Nürnberg 9,040 tons; the Leipzig was 580 ft long and the Nürnberg 594 ft.

References :

2/. https://rwhiston.wordpress.com/2010/04/02/4/ “China’s Sunken Warships – Part 3” (Sect 9. Technology Compromise).

3/. http://www.deutschland-class.dk/deutschland_luetzow/deutschland_luetzow_operation_hist.html

Addendum B

The following website gives an exhautive listing of the Deutschland’s (later the Lützow), activites in log format (http://www.deutschland-class.dk/deutschland_luetzow/deutschland_luetzow_operation_hist.html ) The operational log of the Deutschland shows she was lauched 1931,and served 4 tours of duty in the Mediterranean with the Admiral Sheer and Graff Spee from 1936 to 1939. She then took an active part in the invasion of Norway, and variously escorted the Tripitz, Gneisenau and Hipper in raiding Arctic convoys to Russia 1941 -1 1941). She ended her days scuttled in May 1945 in the Oder river mouth (Baltic Sea), as Germany was overwhelmed from the east.

The following is an excerpt from that log of the Deutschland;

29 May 1937, at 18.40 hrs

Alarm was raised when four Republican destroyers and two light cruisers, Libertad and Mendez-Nunez, were seen approaching, and immediately afterwards two aircraft were reported 2 km astern, attacking out of the sun at an altitude of 1.000 m. Two 50 kg bombs struck Deutschland while the destroyers, initially closing the German Panzerschiff as if to torpedo, opened an inaccurate fire with their forward armament, the shells falling short. The first bomb hit the roof of Starboard III 15 cm gunhouse, splinters puncturing the fuel tank of the floatplane on the catapult. The leaking aviation spirit caught fire in the area of the Senior NCOs’ mess. A motor launch and the aircraft were destroyed.

The second bomb had a devastating effect, penetrating as far as the “tween” deck at Frame 116, the ensuing explosion and fire destroying the upper deck between Frames 94 and 145. A jet of flame ignited oil and spirits beyond an open bulkhead door at Frame 121 and this fire spread rapidly. The forward 15 cm magazine was flooded immediately as a precaution. The worst of the casualties occurred to the personnel of “A” turret, and it was twenty minutes before these guns could be trained on the approaching Republican destroyers, which ceased fire and turned away when ready ammunition for the 15 cm starboard battery exploded at 1930. At the time of the disaster no special state of alert was in effect aboard Deutschland and the AA guns were probably not manned – a grave omission after the warning in Mallorca a few days previously.

The final casualty list was 31 dead and 110 wounded, 71 seriously, these being mostly burn cases.

29 May 1937, at 1935,

Situation was under control and allowed Deutschland to weigh anchor and sail for a rendezvous with Admiral Scheer off Formentera. The final casualty list was 31 dead and 110 wounded, 71 seriously, these being mostly burn cases.

30 May 1937

As a reprisal for the attack, on 31 May Admiral Scheer bombarded the harbour at Almeria. Meanwhile Deutschland had landed 35 seriously wounded at Gibraltar.

31 May 1937

A further 34 wounded was being put ashore when Deutschland was ordered to sea.

Lucky Ship

Some ships are said to be ‘lucky’ – the Lutzow was never that, and nor did she fulfill her potential.

For instance, she was badly damaged in the opening shots of “Operation Weserubung”, the German invasion of Denmark and Norway. At dawn on the very first day (April 9th 1940), the Lützow was ‘line astern’ at 7 knots behind the German heavy cruiser Blücher (18,200 tons), because of the darkness and sandbanks. Their battle group which also included the Emden, Möwe, Albatros, and Kondor entered the fiord that led directly to the capital, Oslo. As the cruiser Blücher approached the Drøbak Narrows she was illuminated by shore line searchlights and was immediately hit by 11” shells from the shore batteries. Her 105 mm ammunition magazine exploded and within minutes she was disabled. After then being hit by two shore based torpedoes she capsized at 07.32 hrs and sank.

Seeing this, the Lützow went astern. She too had been badly hit. Her armour plate and decking had been pierced 15 times by the 6” shells of the Norwegian gun batteries setting the ship on fire below decks.

With the immediate damage brought under control and with Norwegian land forces quickly overrun the Lützow – still able to maintain 24 knots – sailed the following afternoon (10th) for repairs at Kiel.

En route, in the Skagerrak (sea), between Sweden and Jutland she was intercepted by the submarine HMS Spearfish on April 11th. Only one of the four torpedo she fired hit the Lützow. However, it was dead astern and had the effect of, quote, “knocking off both screws (propellers) and the rudder.”

Lützow was dead in the water and slowly sinking, stern first. Tugs reached her a day later and under tow she eventually reached Kiel naval repair yard on April 14th.

She was more badly damaged than anticipated. Her hull amour belt had failed, the hull had split open and was nearly in two pieces (the stern hanging on by the proverbial thread, as can be seen in the pictue below).

Repairs were thus not completed until 31st March 1941. During those 11 months she was decommissioned.

Repairs were thus not completed until 31st March 1941. During those 11 months she was decommissioned.

She left for Norway on June 12th 1941 with destroyer escorts but on June 13th she was located by a twin engine RAF Beaufort torpedo carrying. She was hit on the port side by the torpedo and took on a 21 degree list. The engine room was severely damaged and all her eight M.A.N. diesels engines were dislodged. With all engines stopped and no electrical power, once again the Lützow was dead in the water. However, the thick swirling smoke was so dense it prevented a second aircraft from making a torpedo run. The pocket battleship was forced to abort her Artic convoy raiding mission and return to Kiel for more repairs. It would be May 1942 before she was again on active service this time in Norwegians waters. On July 3rd 1942 she ran aground and holed herself making her unoperational. By Aug 1942 she was back at the Kiel repair yard.

Only on 30th / 31st Dec 1942 Lützow, together with the Admiral Hipper (18,400 tons), and a screen of destroyers, did properly engage with the enemy at what is referred to as the Battle of the Barents Sea. After this engagement which saw the larger Admiral Hipper severely damaged by smaller British warship, German surface ships were prohibited by Hitler from further skirmishes.

The years 1943 and 1944 were uneventful, spent in the shadow of the actions by Prinz Eugen (18,400 tons), Admiral Hipper (18,400 tons), Scharnhorst (31,500 tons) and Tirpitz (42,900 tons). For her part Lützow spent her time quietly moving from one fiord anchorage to another to confuse enemy reconnasance planes.

It should be noted that there was another German ship named Lützow. As part of the infamous Ribbentrop Pact often referred to as the Non-Aggression Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union (signed secretly on 23rd August 1939), a not quite completed German Hipper Class heavy cruiser, the Lützow, was sold to the USSR on Feb 11th 1940. She was towed, as a hull with only A and D guns in place, from Bremen to the Leningrad ship yard. However, she became a casuality of the subsequent German invasion of that country.

Addendum C

I am indebted to the Gentleman’s Military Interest Club for the following additional material regarding the disposition of Germans naval units in the Mediterranean between 1936 and 1939 (GMIC http://gmic.co.uk/index.php?showtopic=21780).

A number of German warship were known to be operating in the Mediterranean during the Spanish Civil War and these have been cited earlier both in the text and the first Table. In the previous sections (8. Photo Gallery) additional photographs of some of these warships have been included.

GMIC source indicates that in the same month as the outbreak of hostilities, i.e. in July 1936, ships of the German fleet were in the region. As previously mentioned the most notable of these surface German warships were the Admiral Graf Spee, the Admiral Scheer, the Deutschland, and light cruiser Koln.

At the time these represented the capital ships at Germany’s command and they were escorted by a flotilla of smaller warships, the ‘2nd Torpedo-boat Flotilla’ (2 T Flotilla). This flotilla was made up of four boats; the Seeadler, the Albatros, the Luchs and the Leopard. The Luchs and Leopard were classified as “Torpedo-boats”, however, this does not infer MTB type craft but much larger corvette sized vessels. The Admiral Graf Spee, Deutschland, Leopard, Albatros and Koln can be found in the first table.

The ‘Saltzwedel Flotilla’ represented Germany’s underwater presence and their primary task was to enforce the blockading of ports and deter ships from trading.

Unterseebootsflottille “Saltzwedel” (1936 – 1939), the U-Flotilla “Saltzwedel” was founded on 1 Sept 1936 under the command of Fregkpt. Scheer

The type of U-boats selected for this mission were the new Type VIIA (which were only available in small numbers to the 2nd Saltzwedel Flotilla). Type VIIA U-Boats were built between 1935 and 1937 so when they were deployed they were very new vessels and virtually untested. They carried 11 torpedoes, were 211 feet long (64.51 mtrs) and had a displacement of 915 tons.

The other type of U Boat available at the time was the Type II which was considerably smaller at 140 feet long, had a displacement of 414 tons and carried only half as many torpedoes. Operating at some distance from Germany and initially with the only friendly ports being in Italy, the ocean going Type VIIA boat was preferred over the smaller Type II designed for coastal waters.

From being sympathetic towards the Franco regime in July 1936 Germany had moved by Sept, to planning for covert naval operations on behalf of Franco using elements of the 2nd Flotilla Saltzwedel. Surface ships could not be used as they would be too readily identified and sunk by the International force.

“Operation Ursula” was the name given to this covert campaign to be waged by U-boats against a small number of targets (Republican shipping and warships). The existence of “Operation Ursula” only became known when a French naval officer, Claude Houan, began investigating Kreigmarine documents after World War II (even the Franco regime was unaware of its existence).

The intended force operating in the Mediterranean was to be the ten U-Boats of the 2nd Flotilla “Saltzwedel” comprised by the following:

U-27, U-28, U-29, U-30, U-31, U-32, U-33, U-34, U-35 & U-36

-

U-27 – U-32 were type VIIA and built between 1935 and 1937.

-

U-33 – U-36 were type VIIA and built between 1935 and 1936.

-

U-37 – U-44 were type IX and built between 1936 and 1939.

The first planned phase was to send five U-Boats into the Mediterranean; U-27, U-28, U-30, U-33 & U-34. However, at the last moment U-30 appears to have been discarded or ‘pulled’ as a candidate by the German command.

In the event two U-Boats left Germany in Nov 1936 for the Mediterranean – the U-33 and the U-34. The Kreigmarine assigned them the codenames Triton and Poseidon, respectively.

Both U-33 and U-34 had a miserable time in the Mediterranean with torpedoes not finding their target or not exploding. The lack of success brought, in Dec 1936, a recall from Berlin. However, en route U-34, saw the outline of a C class Spanish submarine on the surface and sank it (U-34 is pictured above). The submarine was the ‘C 3’ and the discovery by Claude Hogan brought to an end the speculation of just what had caused the C 3 to go missing (the wreck of C 3 lay undiscovered until 1998). In general it would be fair to say that almost all sinkings by submarine were the result of action by the Italian navy.

In the spring of 1937, the U-boats of the Saltzwedel flotilla returned to the Mediterranean, but this time as part of overt international surveillance operations. The captain of U-33, Kapitänleutnant Kurt Freiwald, was re-assigned to U-21 in Jan 1937. within a few months, June 1937, he was re-assigned back to U-33 but only until July 25th. This is an exceptional event and one explanation is that it was another secret mission, the nature of which no one knows.

Refs:

- Gentleman’s Military Interest Club http://gmic.co.uk/index.php?showtopic=21780).

- U-Boat net http://www.uboat.net/articles/index.html?article=59

- “Operation Ursula” and the sinking of the submarine C-3, by Julio de la Vega http://www.uboat.net/articles/index.html?article=59

- Additions:

HMS Fury. New information points to this F-class destroyer also being a participant in the International Non-Intervention force of 1936. When King Edward VIII abdicatied the British throne to marry Mrs. Simpson in 1936, it was HMS Fury that carried him to France and into permanent exile.

KMS Nurnburg. The Nurnburg served in 1936 as part of the International Non-Intervention Force during the Spanish Civil war. She was a brand new ship, commissioned a year earlier in 1935, capable of 32 knots and the only vessel in the Nurnburg light cruiser class. At the outbreak of World War 2 (Sept  1939), the Nurnburg started mining duties in the North Sea. She later moved into Norwegian waters as part of the Fleet training Squadron and mining service in the Baltic. The main armament of the 9,040 ton Nurnburg were 3 turrets of 6” guns (15 cm) and 8 × 3.5” (8.8 cm), plus torpedoes. At the stern she had 2 turrets, ‘X’ and’Y’ but at the bow only one faced forwards (‘A’ turret). In 1944 and 1945 the Nurnburg assisted the Army and transported refugees from the east. She surrendered at Copenhagen on 9th May 1945. On the 5th January 1946 she was given to Russia at Libau (a fate that befell several ships including the Deutchland) and incorporated into the Russian navy as the Admiral Makarov. She was finally broken up in 1959.

1939), the Nurnburg started mining duties in the North Sea. She later moved into Norwegian waters as part of the Fleet training Squadron and mining service in the Baltic. The main armament of the 9,040 ton Nurnburg were 3 turrets of 6” guns (15 cm) and 8 × 3.5” (8.8 cm), plus torpedoes. At the stern she had 2 turrets, ‘X’ and’Y’ but at the bow only one faced forwards (‘A’ turret). In 1944 and 1945 the Nurnburg assisted the Army and transported refugees from the east. She surrendered at Copenhagen on 9th May 1945. On the 5th January 1946 she was given to Russia at Libau (a fate that befell several ships including the Deutchland) and incorporated into the Russian navy as the Admiral Makarov. She was finally broken up in 1959.

- Correction:

Torricelli: The Italian Brin class submarine has, in this article been mis-spelt and is wrongly refrred to as the Torcellini (see first table). Unfortunately, I am not the only one to have made this mistake, some sources have it as Torricelli and others as Torcellini. The correct name for this submarine is “Torricelli.” The situation is further confused, I am informed by Ignacio Recalde (Spain), by the same verssel being known alternatively as 1/. Torricelli, 2/. General Mola, 3/. C-3, 4/. C-5, 5/. Mola, 6/. General Mola II.

Addendum – Jan 2012. I am grateful to Andrew Eccles for his additional information regarding HMS Barham (rec’d Jan 2012), which awas also part of the International Navaal force. I had a supicion that more then just Repulse, Resolution, Queen Elizabeth etc, took part, so I am grateful for his new information. Andrew’s reference in his comment below reveals perhaps the best ever image of HMS Barham entering Grand Harbour in Valletta, Malta. I invite readers to discover why Andrew says ‘tricolours’ stripes appear on B turret – an obvious necessity during the emergency – which I was unaware of and which I had not found in other sources.

HMS Barham entering Grand Harbour in Valletta, Malta. Courtesy of http://www.shipspotting.com/gallery/photo.php?lid=299268

Gold : Nazi Germany’s War Effort and the BIS

Germany acquired more gold bullion to back its currency its currency and raise its credit rating every time if invaded another country. Aggression funded Germany’s expansion westwards, eastwards and gave it the ability to tackle Russia.

The Spanish link was this; during and prior to World War II, Sweden did not accept gold as payment for supplying raw materials and the Swiss would accept only gold. They did not accept German paper money. Together with Spain and Portugal, these 4 countries, one suspects, facilitated Nazi purchasing and payments to 3rd parties, i.e. money laundering, avoiding the belligerent status embargoes then in force by the Allies. Was this payback for Germany’s support of Franco during the Spanish Civil War ?

After Stalin had acquired Spains gold reserves he had designs on the gold reserves of other European countries, an ambition he shared with Hitler. As part of the Non-Aggression Pact which the two socialist states had signed, the prospect of Lithuanian and Latvian gold seemed within Stalin’s grasp. But delays in bi-lateral trade talks and then the invasion of Russia put paid to that ambition (this might account for Stalin’s apparent disbelief at being invaded).

In 1938 the BIS (created in 1930 to facilitate inter central bank transfers), played a pivotal role in Germany’s acquisition of $13.5m of the Czech state’s gold.

When Austria was annexed – again in 1938 – her gold was transferred to the Reichsbank.

The Germans were cleverly mis-using the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) to convey either physically to Berlin or by crediting the Reichsbank account with other nation’s gold. Even the Bank of England was forced to be complicit in these monetary operations both before and during the war.

With the invasion of Poland, which had $64m in gold, the Germans were not so lucky. It ended up with Belgium’s gold in Dakar, a Vichy French colony in West Africa.

But little Danzig, on the Baltic coast, earned the Nazi invaders $4m in gold.

Westwards, Germany took Belgian and Dutch gold reserves. Some Belgian gold also ended up in Dakar. After the fall of France its journey to West Africa in 1941 and its erturn passage is comparable with any Indiana Jones tale. After an expedition ‘up country’ to Timbutu, then down the Niger River and across the Sahara, a fleet of Vichy aircraft shipped the 240 tons of gold, two tons at a time, from Algiers to Marseilles.

The failed invasion of Dakar by Free French forces in Sept 1940, backed by a large Royal Navy fleet was in response to the possibility of the Vichy France warships joining the German navy. Rarely is the 2nd purpose, namely the securing of the gold bullion, mentioned in commentaries. Vichy France’s sympathies were revealed when 4 days later 50 Vichy French aircraft bombed Gibraltar.

France’s central bank was a popular option (but as it turned out a poor one) among central banks of several European nations. For while the French government was able to whisk away 3,000 cases of French gold to Canada in March 1940 aboard the battleship Bretagne, escorted by the cruiser  Algérie, presumably to avoid it being impounded by the then still neutral USA. France’s depositing customers were not so lucky !

Algérie, presumably to avoid it being impounded by the then still neutral USA. France’s depositing customers were not so lucky !

Right: Franch heavy cruiser Algérie.

The Netherlands gold reserves of $163m fell into German hands. The Dutch also had to agree to pay 50 million Reichsmarks per month for Germany’s offensive against Bolshevism – of which 10 million Reichsmarks had to be in gold.

Germany’s subsequent invasion of Norway and Denmark brought her $88 million and $51m respectively. Luxembourg yielded $4.8m in gold for Berlin.

France had $245 m which was held in French Martinique and a further $260m held in the Federal Reserve in New York. The accounts were known to Berlin. Germans thinking was that even with Vichy France compliance the US would seek to grab the horde.

With the fall of France, America took steps to freeze the New York deposit and the Martinique gold reserve, under its Vichy Governor, stayed where it was.

The invasion of Yugoslavia, the Balkans and Greece in 1941 probably brought more gold to the Reichsbank.

Concentration camps also yielded gold, other precious metal and precious stones with a street value.

By September 1943 Germany had occupied and looted Albania and even with Italy collapsing in 1943, Germany moved Rome’s gold to Berlin (some $88m).

The state’s operations threought official channels were supplemented by specific German army army units whose task it was to loot and raid High Street banks in occupied countries removing any gold, jewellery and precious stones or tradable securities, e.g. bearer bonds. etc.

With the imminent fall of Berlin in 1945, most of her remaining gold reserves, worth some $238 million, and a large quantity of the monetary reserves, were moved to a potassium mine already used by the SS for hording miscellaneous valuables.

One can imagine Hitler’s phobia of Bolshevism (and the Soviet Union) manifesting itself in denying them in their hour of victory against him any gold bullion to show as a reward. A programme of gold dispersal away from Berlin was certainly a Reichsbank procedure before 1939 and one has to imagine this planning continued during the war.